Appendix G - Student Focus Group Summary

Appendix G Student Focus Groups Sum.docx

2023-24 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:24) Full-Scale Study - Institution Contacting and List Collection

Appendix G - Student Focus Group Summary

OMB: 1850-0666

2023–24 NATIONAL POSTSECONDARY STUDENT AID STUDY (NPSAS:24)

Student Data Collection and Student Records

Appendix G

Student Focus Group Summary

OMB # 1850-0666 v.34

Submitted by

National Center for Education Statistics

U.S. Department of Education

September 2022

Contents

Topic 1: Nonstandard Work and Gig Jobs – General G-7

Topic 2: Nonstandard Work and Gig Jobs – Specific G-8

Topic 3: Experiences During COVID-19 G-10

Topic 4: Data Collection Materials and Communication Methods G-10

Recommendations for the Field Test Study G-12

Data Collection Materials and Communication Methods G-12

Tables

Figures

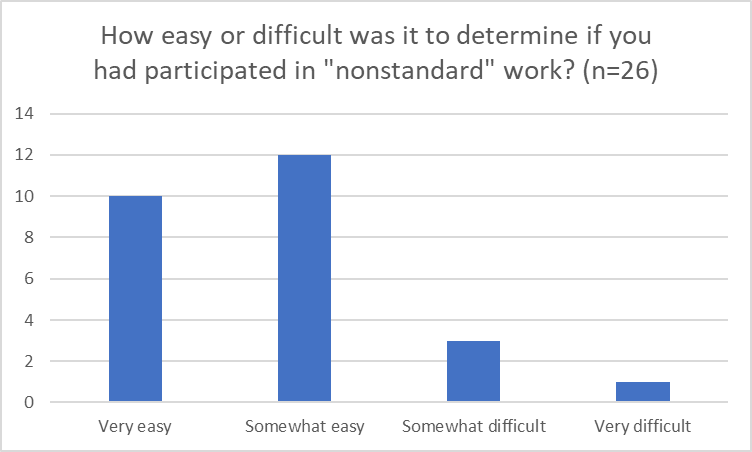

Figure 1. Ease of determining engagement in "nonstandard" work G-9

This appendix summarizes the results of qualitative testing conducted in preparation for the 2023-24 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:24) Field Test Student Survey. Full details of the pretesting components were described and approved in NPSAS:24 generic clearance package (OMB# 1850-0803 v. 317). Virtual focus group participants tested, evaluated, and provided feedback on select existing and proposed NPSAS:24 student survey topics (e.g., nonstandard gig work and COVID-19 experiences), to improve the survey by making it clearer and easier to understand. Additionally, participants discussed several survey contacting methods and shared their opinions on invitations to participate in surveys. A summary of key findings is described first, followed by a detailed description of the study design, a discussion of detailed findings from the focus group sessions, and final recommendations.

A total of 26 students participated in four online focus groups (ranging from four to nine participants per group) between June 23 and July 1, 2022. Of these, 50% were female and 50% were male. Over one-third (38.5%) of participants were between the ages of 18 and 24, and another 23% were between the ages of 25 and 29, with the remainder (38.5%) between 30 and 49 years of age. Furthermore, about one quarter of the participants (27%) identified as White, another quarter (27%) identified as Asian, 19% identified as African American, 15% identified as Hispanic or Spanish Origin, and 11.5% identified as Mixed Race (one or more race).

Overall, most participants reported a general understanding of what gig work is, defining it as “jobs with flexibility in scheduling and where the employee had the ability to control how much they would want to work” and provided specific examples of companies that accommodate gig workers. However, when comparing the terms “gig work” and “nonstandard work”, some participants described these as two different types of work. Additionally, participants reported that recalling the number of hours worked in nonstandard jobs becomes more difficult over a longer timeframe due to the inconsistency of the hours worked, which they reported varies daily, weekly, and monthly. Similarly, reporting gig income in terms of a percentage of their total income was difficult to calculate, leaving many to “guesstimate.” In general, participants reported using the income from nonstandard gigs as income for basic necessities as well as additional income for items they may not otherwise purchase.

Experiences During COVID-19

Not surprisingly, the participants reported many effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in their personal lives and their enrollment in school. These effects included changing campuses to be closer to family, changing institutions for access to more online courses, switching to virtual formats, and social distancing. Participants claimed that nonstandard gig work became more popular due to increasing unemployment rates and social distancing requirements.

Data Collection Methods

Participants stated that the use of incentives was one of the main factors they would consider when deciding whether to participate in the NPSAS survey. Other factors include:

clearly evident and reliable source (e.g., “.gov” and “.edu” e-mail domains)

subject lines mentioning incentives

Factors that decrease desire to participate include:

lack of incentives

lengthy surveys

QR codes that may not work on certain phones, or the extra step of having to scan the entire code

lengthy letters

phone calls

excessive use of emojis, exclamation marks, and non-standard fonts

Many reported hesitancy to open texts or e-mails from unknown sources due to the prevalence of spam and phishing incidents. When receiving an e-mail from an unknown source, participants mentioned conducting an online search to find out more about the source or ignoring the text or e-mail entirely.

In collaboration with the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), RTI International (RTI) is preparing to conduct the next round of data collection for the National Postsecondary Aid Study (NPSAS), a nationally representative study of how students and their families pay for postsecondary education. The purpose of the online focus group sessions is for participants to test, evaluate, and provide feedback on select survey questions from NPSAS:24 to improve the student survey.

Additionally, RTI seeks to optimize recruitment of the target respondents by investigating participant attitudes toward survey-related communication. Therefore, EurekaFacts conducted focus groups with postsecondary students to obtain feedback on the following data to refine the NPSAS student survey and recruitment processes:

Assessing and refining gig work survey items

Understanding student experiences during COVID-19

Soliciting feedback on student contacting materials

A sample of 26 participants who were currently enrolled or enrolled in a college, university, or trade school between July 1, 2020 and the time of testing (June 2022) participated in the present study. Table 1 provides a summary of participants’ demographics:

Table 1. Participant Demographics

Participants’ Demographics |

Total |

Percent (n = 26) |

Gender |

|

|

Male |

13 |

50% |

Female |

13 |

50% |

|

|

|

Age |

|

|

18-24 |

10 |

38% |

25-29 |

6 |

23% |

30-34 |

5 |

19% |

35-39 |

3 |

12% |

40-49 |

2 |

8% |

|

|

|

Race/Ethnicity |

|

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

0 |

0% |

Asian |

7 |

27% |

Black or African American |

5 |

19% |

Hispanic or Spanish Origin |

4 |

15% |

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander |

0 |

0% |

White |

7 |

27% |

Mixed Race (One or more race) |

3 |

12% |

|

|

|

Degree Program or Course Type |

|

|

Undergraduate certificate or diploma, including those leading to a certification or license |

1 |

4% |

Associate’s degree |

8 |

30% |

Bachelor’s degree |

10 |

38% |

Master's degree |

4 |

15% |

Doctoral degree—professional practice |

1 |

4% |

Doctoral degree—research/scholarship |

1 |

4% |

Graduate level classes (not in a degree program) |

1 |

4% |

|

|

|

Annual Income |

|

|

Less than $20,000 |

6 |

23% |

$20,000 to $49,000 |

12 |

46% |

$50,000 to $99,000 |

4 |

15% |

$100,000 or more |

3 |

12% |

Prefer not to answer |

1 |

4% |

To qualify for participation, each respondent had to be enrolled in a college, university, or trade school at some point between July 1, 2020 and the start of testing (June 2022).

EurekaFacts drew participants from an internal panel of individuals as well as targeted recruitment to individuals aged between 18 and 49 years old across the country. All recruitment materials, including initial outreach communications, study advertisements and flyers, reminder and confirmation e-mails, and informed consent forms, underwent OMB approval. Recruitment materials and advertisements were distributed across social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. All potential participants completed an OMB approved online eligibility screening. During screening, all participants were provided with a clear description of the research, including its burden, confidentiality procedures, and an explanation of any potential risks associated with their participation in the study. Qualified participants whose self-screener responses fully complied with the specified criteria were then contacted by phone or e-mail and scheduled to participate in a focus group session. While not an explicit eligibility requirement, participants were able to self-identify as being employed as a gig worker within this survey.

Participants were recruited to maintain a mix of demographics, including gender, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, as shown in Table 1. Each focus group included four to nine participants for a total of 26 participants across the four focus groups. All focus group participants received a $75 incentive as a token of appreciation for their efforts.

Ensuring participation

To ensure maximum “show rates,” participants received a confirmation e-mail that included the date, time, and link to access the online focus group. Additionally, participants that were scheduled more than two days prior to the actual date of the session received a reminder e-mail 48 hours prior to the focus group session. All participants received a follow-up e-mail confirmation and a reminder telephone call at least 24 hours prior to their focus group session, to confirm participation and respond to any questions.

EurekaFacts conducted four 90-minute virtual focus groups over Zoom between June 23 and July 1, 2022. All four focus groups were comprised of participants who self-identified as employed as a gig-worker, to obtain survey feedback from college students who have participated in that type of employment.

Data collection followed standardized policies and procedures to ensure privacy, security, and confidentiality. Participants submitted consent forms before the start of their session. Once logged into Zoom, participants were admitted into the session from the virtual waiting room. They were then welcomed and asked to complete a visual and audio check of their desktop/laptop. The consent forms, which include the participants’ names, were stored separately from their focus group data, and were secured for the duration of the study. The consent forms will be destroyed three months after the final report is released.

Focus Group Procedure

At the scheduled start time of the session, participants logged into the virtual Zoom meeting room. After participants were admitted into the meeting room, they were reassured that their participation was voluntary and that their answers may be used only for statistical purposes and may not be disclosed, or used, in identifiable form for any other purpose except as required by law.

Focus group sessions progressed according to an OMB-approved script and moderator guide. The participants were informed that the focus group session would take up to 90 minutes to complete and was divided into two sections: a short online survey and a period of group discussion. After participants completed the 10-minute survey, the moderator guided participant introductions before initiating the topic area discussion.

The moderator guide was used to steer discussion toward the specific questions of interest within each topic area. The focus group structure was fluid and participants were encouraged to speak openly and freely. The moderator used a flexible approach in guiding the focus group discussion, as each group of participants was different and required different strategies.

The following topics were discussed in the focus groups:

Topic 1: Nonstandard work and gig jobs – general

Topic 2: Nonstandard work and gig jobs – specific

Topic 3: Experiences during COVID-19

Topic 4: Data collection materials and communication methods

The goal of the discussion was to assess and refine survey items by gaining an understanding of the participants’ interpretation of the gig economy and experiences during COVID-19, as well as to solicit feedback on student contacting materials. At the end of the focus group session, participants were thanked, and reminded that their incentive would be sent to them via e-mail.

The focus group sessions were audio and video recorded using Zoom. After each session, the moderator drafted a high-level summary of the sessions’ main themes, trends, and patterns raised during the discussion of each topic. A coder documented participants’ discussion and took note of key participant behaviors in a standardized datafile. In doing so, the coder looked for patterns in ideas expressed, associations among ideas, justifications, and explanations. The coder considered both the individual responses and the group interaction, evaluating participants’ responses for consensus, dissensus, and resonance. The coder’s documentation of participant comments and behavior include only records of participants’ verbal reports and behaviors, without any interpretation. This format allowed easy analysis across multiple focus groups.

Following the focus group, the datafile was reviewed by two reviewers. One of these reviewers cleaned the datafile by reviewing the audio/video recording to ensure all themes, trends, and patterns were captured. The second reviewer conducted a spot check of the datafile to ensure quality and final validation of the data captured. Once all the data was cleaned and reviewed, it was analyzed by topic area.

The key findings of this report were based solely on notes taken during and following the focus group discussions. Additionally, some focus group items were administered to only one or two groups and furthermore, even when items were administered to all focus groups, every participant may not have responded to every probe due to time constraints and the voluntary nature of participation, thus limiting the number of respondents providing feedback.

Moreover, focus groups are prone to the possibility of social desirability bias, in which case some participants agree with others simply to “be accepted” or “appear favorable” to others. While impossible to prevent this, the EurekaFacts moderator instructed participants that consensus was not the goal and encouraged participants to speak freely and offer different ideas and opinions throughout the sessions.

Qualitative research seeks to develop insight and direction, rather than obtain quantitatively precise measures. The value of qualitative focus groups is demonstrated in their ability to provide unfiltered comments from a segment of the targeted population. While focus groups cannot provide definitive answers, the sessions can play a large role in gauging the usability and functionality of the online survey, as well as identifying any consistently problematic survey items and response options.

This section discusses the participants’ understanding of what nonstandard gig jobs are and what they are not. Additionally, participants were asked how easy or difficult it was to determine if they had participated in 'nonstandard' work in the past 12 months.

Key Findings

Defining Nonstandard Work and Gig Work

Participants described nonstandard work and gig jobs in a variety of ways, such as jobs with flexibility in scheduling and where the employee had the ability to control how much they would want to work. Participants reported that nonstandard work consisted of nontraditional, "non-brick and mortar work" such as "freelance work" outside the traditional Monday-Friday 9 am-5 pm office job. Popular examples of nonstandard gigs that participants provided included "TaskRabbit, Uber, and Lyft". Some participants indicated thinking of nonstandard work and gig work as separate and distinct types of employment. As one participant stated, “There's a gray line between what is a gig, a nonstandard, and what is standard. There's a blurred line and they overlap each other.”

Additionally, one participant reported their view that, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the nonstandard gig economy has drastically increased due to people being laid off, making these jobs more of the "norm" in our society. They explained that since the pandemic, people's perspectives may have shifted to be more inclusive of these nonstandard jobs.

Determining Participation in Gig Work

Twenty two of the 26 participants reported that it was easy to determine whether they had participated in gig work, stating that the examples provided in the question wording helped them to decide. However, the remaining two reported difficulties in determining whether they have participated in "nonstandard" work or that it was their first time hearing this term.

Figure 1. Ease of determining engagement in "nonstandard" work

Summary

Participants generally found it easy to define and understand what nonstandard gigs are and indicated that it was easy to determine if they had participated in this sort of employment. However, many respondents made a distinction between nonstandard and gig work, so including both terms in question wording would ensure that the survey captured all types of nonstandard and gig work. Furthermore, many participants reported that they enjoy gig jobs and nonstandard work because it allows them flexibility in work hours as well as more freedom.

This focus group topic further explored participation in nonstandard gigs including whether 20 hours a month was a normal amount, and how easy or difficult it was for participants to recall the frequency at which they worked these jobs in the past four or 12 months. Participants discussed the income received from nonstandard gigs by using percentages to determine how much of their total income came from nonstandard gigs. In addition, participants discussed how they used the money earned from nonstandard gigs and why they chose to work a nonstandard job.

Key Findings

20 Hours of Gig Work

"I said it's

a lot [of hours]. Because I was thinking about it in the perspective

of if you're juggling a full class load and you're juggling a full

or part-time job on the side, then that's a lot. But if this is your

main source of work or you're only a part-time student, then it

might not be a lot."

Reporting Hours Worked in Past Four Months vs. 12 Months

While nearly three-quarters of the participants (19 out of 26) indicated it would be very easy or somewhat easy to report the number of hours worked in the past four months, the number shifted to less than half of the participants (12 out of 26) being able to recall the number of hours worked in the past 12 months.

"Like, did

you work X, Y, Z amount of hours within and break it down, like by

months or by quarters, but again, with the knowledge that everyone's

academic year is different."

Providing Percentage of Income from Nonstandard Work

Participants were also asked to provide a percentage range of how much they earned from nonstandard gig work as their total income. When asked to provide percentages on how much of their total income was from nonstandard gig work, a majority of the students reported that it was “somewhat difficult” to calculate. This resulted from the difficulties in tracking their schedules and hours worked that come with the nature of nonstandard jobs.

“I said

somewhat difficult because the consistency in pay on a nonstandard

job can be so varied.”

How Money Earned was Used

When asked to describe how the money earned from nonstandard jobs was used, the participants’ responses ranged from basic everyday necessities, additional income, and to pay for extra items they wanted (e.g., video games, novelties, hobbies, leisure activities). The majority of respondents indicated that they used this income as additional income and did not require this money to meet their basic living needs. Some participants reported that factors contributing to their willingness to participate in nonstandard work was dependent on whether the nonstandard gig was their primary source of income or if the money earned was needed to cover necessities (i.e., food, housing bills, etc.)

Summary

While nearly half of the students reported that 20 hours of nonstandard gig work was a fairly normal number of hours, it must be noted that this will vary significantly depending on whether the student was enrolled as a part-time or full-time student.

When asked to recall hours worked in nonstandard gigs in the past four months, three quarters of the participants reported that it was “very easy” or “easy”. Comparatively, less than half the participants reported it would be “easy” or “very easy” to estimate hours worked over the past 12 months. The participants who declared recalling these hours would be “somewhat difficult” reported that the number of hours they worked varied daily, weekly, and monthly making it difficult to remember. This inconsistency made it a challenge to approximate the hours worked.

Participants commonly stated that they had to "guesstimate" when recalling the amount of money made from nonstandard jobs. This is a caveat of nonstandard jobs, which can, unfortunately, create challenges in collecting accurate numbers and data for this specific type of work.

When asked to describe how the participants used income from nonstandard gigs, participants stated it was additional income used to pay for necessities and extra expenses (i.e., hobbies and leisure activities).

The third topic of the focus group covered the participants’ personal experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly as it relates to enrollment, the ability to complete classwork, attend classes, and personal impacts of COVID-19.

Key Findings

Effects of COVID-19

“I would

say it changed for me because all my classes had to be online. They

were no longer meeting in person, and it was difficult as well

because there was zero childcare for my younger siblings.”

A majority of participants reported that unsecured housing, social distancing requirements, mass unemployment, and the start of more nonstandard gig work were factors they directly experienced from the COVID-19 pandemic. One participant noted that the impact of COVID-19 began in 2020 and that there are still lingering implications.

Summary

Overall, participants indicated that their personal life and enrollment were directly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants noted that nonstandard gig work became more popular due to increasing unemployment rates, social distancing requirements, and switching to virtual formats. It should be emphasized that COVID-19 could heavily influence the data observed on the frequency of nonstandard gig work, and these increases may not be the same if not for the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, the last topic covered aspects of data collection. First, the focus group discussed the methods in which data were collected, including what statements in the material, brochure, or website would discourage students from taking the survey and what statements would encourage participation. Then focus group explored participants’ opinions about receiving texts and e-mails when participating in surveys and what factors would increase or decrease their willingness to participate in a survey.

Key Findings - Data Collection Materials

“I like to

be paid for my time, to be honest with you.”

"For me

seeing it'll take 30 minutes; it'll turn me off from taking the

survey just because 30 minutes is a long time."

"Personally,

I have a disability, and so it's difficult to read and memorize all

this stuff to know what to do. I need things that are concise."

Summary

Participants reported that the use of incentives was one of the biggest indicators of participation. Common factors reported that would decrease participation included lack of incentives, lengthy surveys, and the use of QR codes that may not work on certain phones, or the extra step of having to scan the entire code. Participants reported that lengthy surveys, letters, phone calls, or brochures would deter their desire to participate. The participants stated they would be interested in knowing the source of who is conducting the study and its purpose. Participants reported that they would feel more inclined to participate if it was a reliable source they knew, such as a government agency.

Most participants indicated they would have no issue with the Department of Education contacting them via text.

Permission to Text. Eight participants reported they would grant permission to receive text message reminders, six of whom indicated they would prefer to be contacted by e-mail first. One participant explained, “For me, it’s just like, ‘How did you get my number?’ E-mails are... I don’t know. I guess there’s some kind of place where e-mails are just distributed to everyone. And that’s more of a typical common thing, but if you got my phone number, that’s kind of suspicious.” Furthermore, most of the participants responding (8 out of 11), claimed they may initiate a two-way text exchange to inquire about incentives, expecting a reply ranging from a few hours to three days.

“For me,

it's just like, ‘How did you get my number?’ E-mails

are... I don't know. I guess there's some kind of place where

e-mails are just distributed to everyone. And that's more of a

typical common thing, but if you got my number, that's kind of

suspicious.”

Summary

Many participants reported that they would not have issues receiving text messages from the Department of Education. One added that because it was from the Department of Education, they would be more inclined to open the message assuming it was about loans or registration. When asked what would prompt students to open an e-mail, the most popular response was to mention incentives in the subject line. Many reported that they are hesitant about unknown texts and e-mails due to the frequency of spam and phishing incidents. Participants emphasized the importance of a reliable e-mail or source contacting them and that it increased the likelihood of their response. It should be noted that using certain messages, such as excessive emojis and exclamation marks, may deter participants from responding to texts and e-mails.

Findings suggest that some participants considered "nonstandard work" and "gig job" to be distinct categories, however, this is inconsistent with the intention of these questions. Ideally, the student survey would enable respondents to identify any participation in non-traditional employment regardless of whether they consider it a "gig" or "nonstandard" employment. Therefore, these phrases will be used together in field test question wording (i.e., "gig or nonstandard job"), so that the survey can capture the entirety of a student's employment history. Additionally, the survey will not collect hours worked in this type of employment. Participants found it difficult to accurately provide this information, regardless of timeframe, as there is a great amount of fluctuation in hours worked with this type of arrangement. Instead of hours worked during the academic year, the number of months working gigs and other nonstandard jobs during the academic year of interest will be collected in the field test.

Generally, focus group participants reported similar experiences due to the COVID-19 pandemic as did respondents who were administered these questions in prior studies (i.e., NPSAS:20 and BPS:20/22). Despite some variation in what participants considered a relevant COVID-19 pandemic timeframe, the focus group results indicate that students considered the beginning of the pandemic (March 2020 through December 2020) as relevant in impacting postsecondary education. Given this variation, the NPSAS:24 field test survey will collect COVID-19 impact data for B&B-eligible students, who are most likely to have been enrolled at some point during the pandemic.

Based on findings from the focus groups, field test contact materials will be updated to be more concise, while placing more emphasize on the incentive and NCES sponsorship. E-mails will be sent from a “NPSAS@ed.gov” account to increase legitimacy of the survey request. In addition, the click-here link structure used in e-mails, text messages, and QR codes will be updated so sample members will recognize that these links are associated with the Department of Education. Public forums will also be monitored for any NPSAS-related questions and concerns so that information can be provided to assuage any worries.

| File Type | application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document |

| Author | administrator |

| File Modified | 0000-00-00 |

| File Created | 2023-07-31 |

© 2026 OMB.report | Privacy Policy