Screeners, Pretests and Experiment

Quantitative Research on Front of Package Labeling on Packaged Foods

Appendix A Literature Review FINAL

Screeners, Pretests and Experiment

OMB: 0910-0920

Front of Package Labeling Literature Review

Authors and Contributors

Linda Verrill1, Fanfan Wu1, David Weingaertner1, Taiye Oladipo1, Lisa Lubin1,

Roshni Devchand1, 2Laura Koehler, 2Lauren Prowse, 2Caroline P. Martin, and 3Thea Zimmerman

1FDA; 2Hager Sharp; 3Westat

April 2023

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Results of Key Systematic Reviews (2005 - 2016) 5

Results of Key Systematic Reviews (2016 - 2018) 6

Results of Key Systematic Reviews (2018 - 2021) 10

Results of Key Systematic Reviews (2021 - 2022) 16

Mechanism Used to Manage the Review 36

Appendix C: Summary of Articles included in the FDA Healthy Symbol Literature Review 37

Appendix D: Citations for Studies in the Literature Review 58

BACKGROUND AND CONTENTS

FDA is prioritizing its nutrition initiatives to ensure people in the United States have greater access to healthier foods and nutrition information we can all use to identify healthier choices more easily. Increasing the availability of healthier foods could improve eating patterns and, as a result, improve everyone’s health and wellness.

Claims and symbols can act as quick signals on the front of food packages to help consumers better understand nutrition information and select foods that are part of healthy eating patterns. Other aspects of food labels can provide consumers with further valuable information to help them to identify healthier foods.

To help consumers easily identify packaged foods that would meet an updated definition for the “healthy” claim, FDA is conducting consumer research to develop a “healthy” symbol that could appear on food packages.

FDA is also exploring the development of a nutrition labeling scheme referred to as front of package (FOP) labels displaying a summary of the product’s healthfulness or nutrient content. To support these efforts, FDA conducted and updated reviews of the literature to summarize what is currently known and understood about FOP labeling.

Pages 4 to 10 of this report are the body of the review – the body encompasses 1) a summary of key systematic reviews on FOP symbols, 2) an updated review of the FOP scientific literature, and 3) summaries from guides on government implementation of FOP labels. The Appendices contain: A) a table of FOP labeling schemes and symbols available online and in the scientific literature in 2018; B) the methods report including the study protocol; C) a summary of each article in the updated review; D) citations for articles in the updated review.

LITERATURE REVIEW

General Findings

While the FOP scientific literature is nuanced, the following themes emerged:

A FOP rating system or symbol can help consumers identify and select healthy foods.

Consumers generally prefer simple labels (such as the ones using a summary system).

While more recent studies have examined which type of labels (summary system or nutrient specific) work best, additional research is needed to understand whether consumers’ use of these labels result in healthier diets and better health outcomes.

Some manufacturers have reformulated products following the implementation of FOP nutrition symbols; some evidence suggests increased sales of products bearing a FOP symbol.

Institutional endorsement of logos may be related to greater confidence in the label.

Introduction

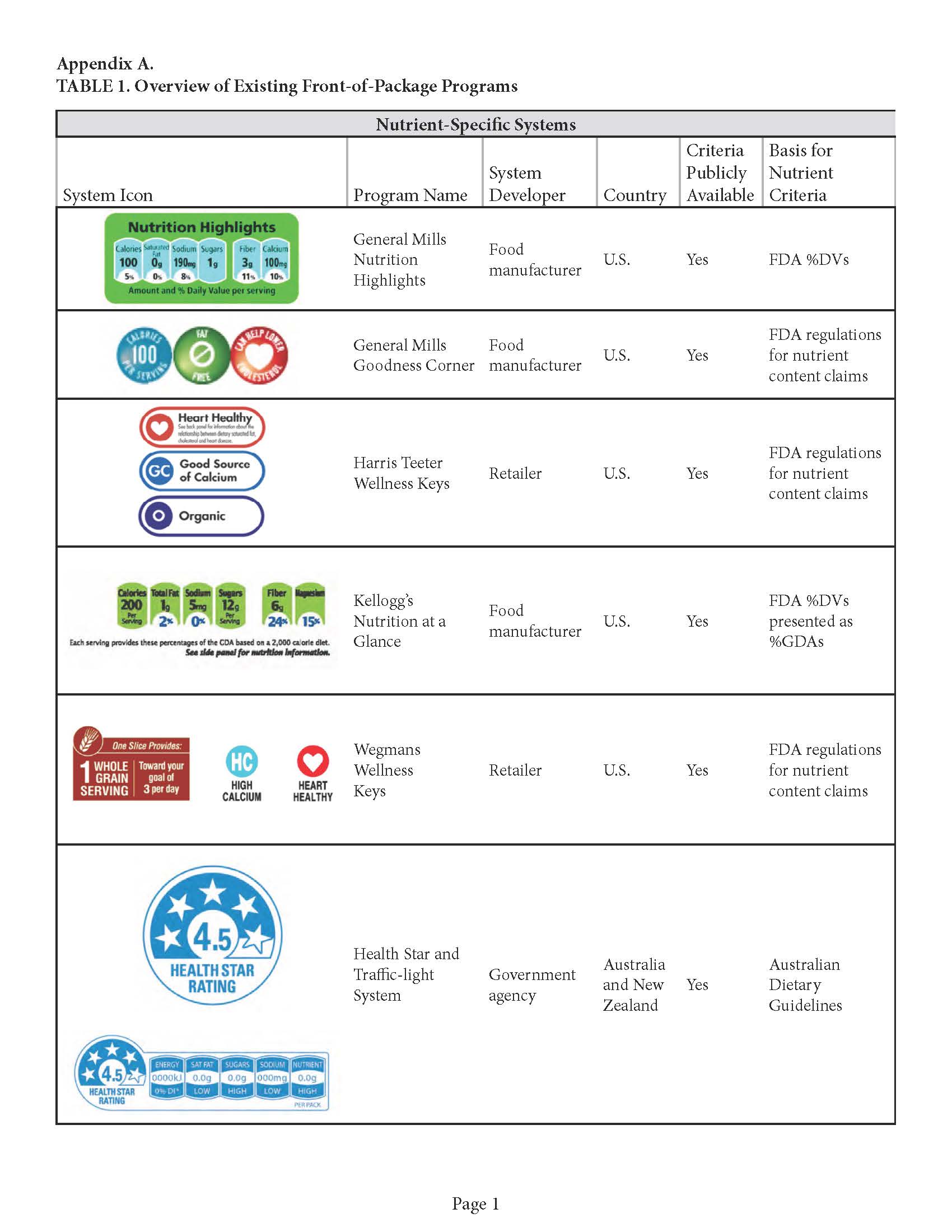

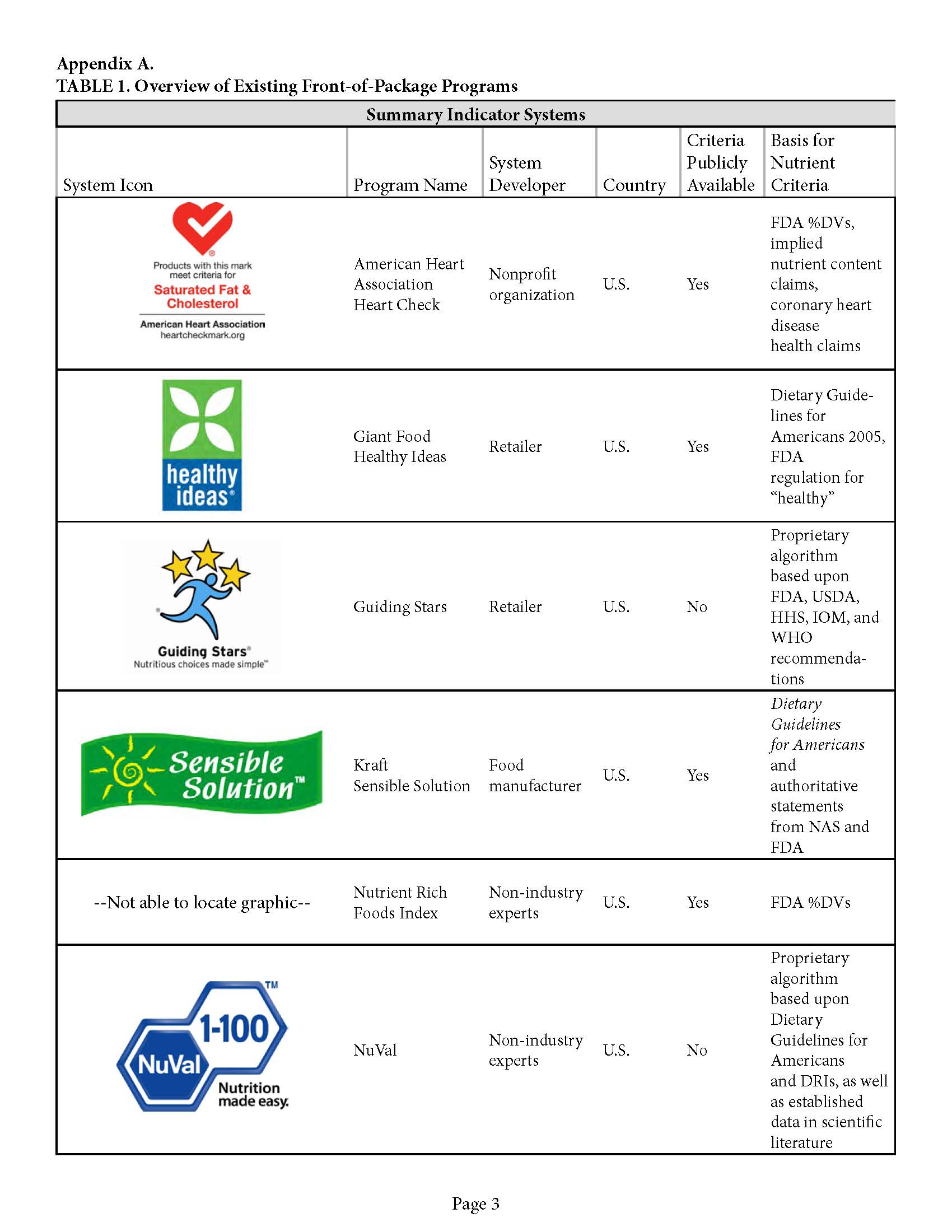

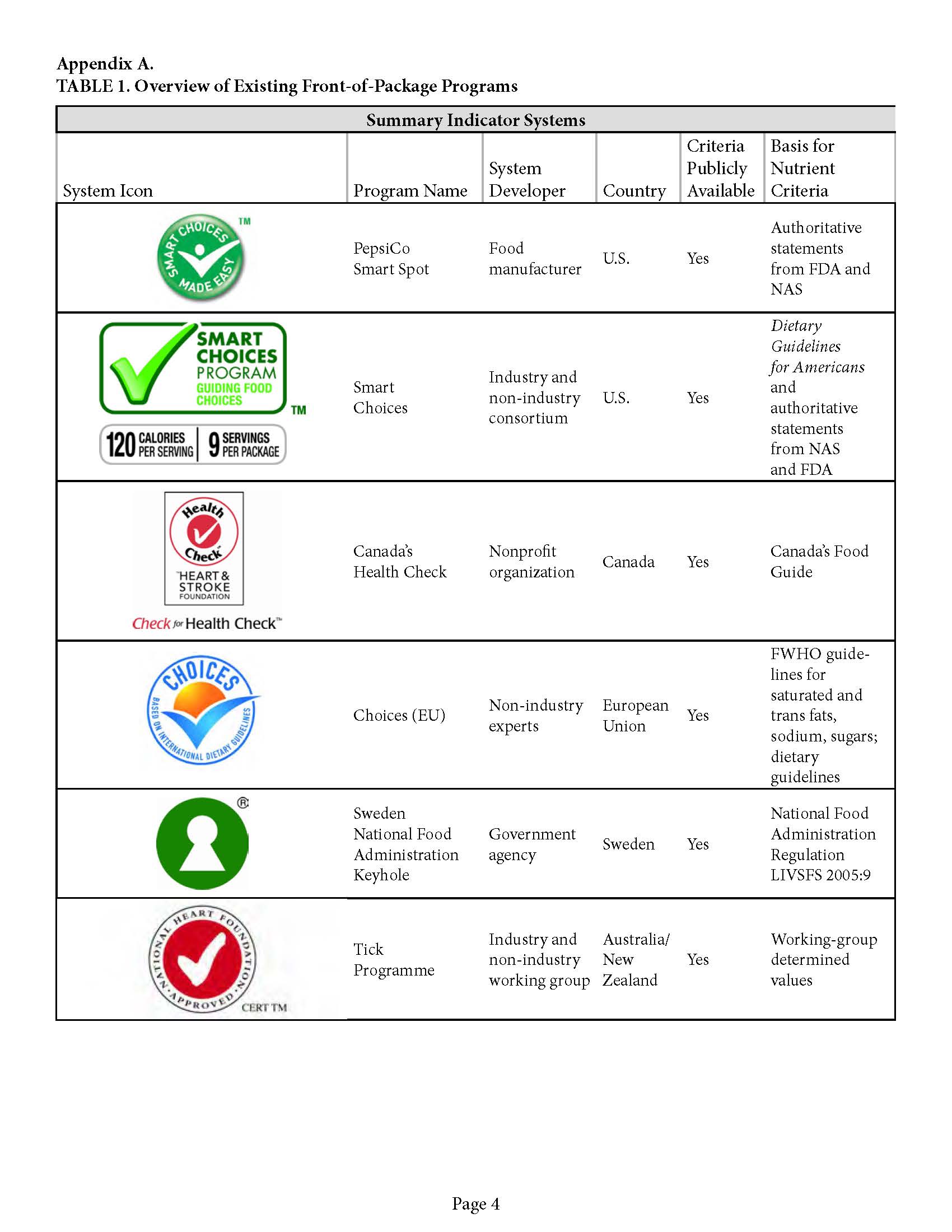

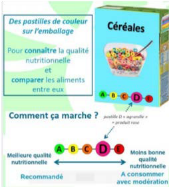

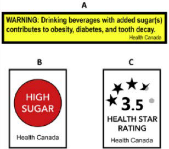

Consumers can use the Nutrition Facts label (NFL) to learn about the product’s nutrients and how a serving of that product fits into the context of their daily diet. In recent years, the market has seen a plethora of nutrition indicators on the front panel of the food label, highlighting nutrients that consumers might want to consume more of or those they might want to limit. These FOP nutrient representations can most easily be grouped into two types: 1) Summary and 2) Nutrient-specific [Andrews et al. 2014] (See Appendix A, Table 1 for examples). Summary indicators are evaluative; that is, they provide an overall interpretive assessment of the healthfulness of a serving of the food, based on a proprietary algorithm. Nutrient-specific indicators, on the other hand, also called “reductive” indicators, are so called because they present a ‘reduced amount’ of the product’s nutrient content on the front of the package.

The scientific literature on FOP nutrition labeling has been the subject of several reviews and reports; we review and summarize them below, and then provide an update of the recent literature (2016 to 2019).

Results of Key Systematic Reviews (2005 to 2016)

A 2005 literature review on consumer understanding and use of nutrition labeling summarized more than 100 studies on NFL usage and FOP nutrition information [Cowburn and Stockley, 2005]. This review was one of the first to conclude that, although consumers report high usage of the NFL, actual usage is likely much lower. The studies reviewed showed that consumers could perform information retrieval tasks and simple calculations using the NFL but it was difficult for them to fully interpret nutrition information on the food label. The review concluded that interpretational aids could contribute to consumers making healthy point-of-purchase choices and moreover, that these aids could help consumers interpret the contribution of the food to the overall diet.

The first large systematic review of FOP nutrient indicators was conducted by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM, formerly the Institute of Medicine (IOM) IOMa, 2010). This report, requested by the U.S. Congress, evaluated the international landscape on FOP nutrition symbols generated by manufacturers, supermarkets, organizations, and governments. The report discusses three types of FOP symbols: 1) Nutrient-Specific Systems; 2) Summary Indicator Systems; and 3) Food Group Information Systems. The overall conclusion was that a FOP rating system or symbol could help consumers identify and select healthy foods, that calories and serving size would be helpful to include in the symbol, and that further testing of consumer use and understanding of “nutrient-specific information” or a “summary indicator” would be necessary. The NASEM report also concluded that a FOP symbol should be geared toward the general population.

The NASEM followed up the report with a Phase II report (IOMb, 2012), focused on consumers’ use of FOP symbols. The Phase II report concluded that, for a FOP symbol to encourage healthier food choices, a simple FOP summary symbol “…that serves as a signal or cue…” would be better than detailed information about nutrient content; the Phase II report recommended “…shifting from an informational approach to an interpretive one…,” and asserted that a successful symbol system would encourage product reformulation or development of products that meet the criteria.

Meanwhile, FDA commissioned a literature review to update the 2005 literature review discussed above. The 2011 FDA review (published by Hersey, et al. 2013) consisted solely of scientific studies on FOP and Shelf Label Nutrition Systems - to learn which types of FOP systems are most effective for influencing healthy food choices. Analysts searched 17 literature databases (e.g., PubMed, Web of Science, ScienceDirect) using a targeted search algorithm. Thirty-eight out of 111 articles were retained for inclusion in the review. This literature review found that summary systems incorporating text and color worked better than those using only numeric information in attracting consumer attention and getting them to make healthier food choices - but that the nutrient-specific systems (the reductive indicators) worked better than the single summaries for providing consumers with details about what made the food healthy.

In 2016, FDA commissioned an update to the 2011 literature review discussed in the previous paragraph. This update captured the scientific literature on FOP from 2010 to August 2016 (RTI, 2016). Following the format of the previous literature reviews, the Addendum examined 79 articles and summarized them using the same categories identified in earlier reviews. Similar to previous reviews, the Addendum reported that 1) the literature suggests that graphic elements help consumers with food purchase decisions; 2) consumers – especially diverse subpopulations - prefer simple labels over those that have numerical information; 3) color coding with some text leads to better understanding of the nutrition information; 4) there is not enough evidence to indicate exactly which type of FOP label most influences consumers behavior; and 5) there is some evidence that FOP labels influence sales but no evidence on whether they lead to decreasing consumption of nutrients to limit or increasing consumption of nutrients to get enough of.

Results of Key Systematic Reviews (2016 to 2018)

The FDA updated the 2016 FOP literature review by reviewing the scientific literature on FOP from August 2016 to October 2018, using the same targeted database search algorithm and the analytical categories used in earlier reviews. Fifty-one scientific articles on FOP were analyzed for this FOP literature update. Table 1 below presents the highlights and conclusions of this literature review by analytical category.

Table 1. Highlights and Conclusions of updated FOP nutrition labeling literature by analytical category (August 2016 to October 2018)

Analytical category |

Highlights and conclusions |

Attention and Processing |

Conclusion: These studies extend the findings of the 2016 RTI Addendum which found that FOP labels catch consumers’ attention; the newer studies highlighted interactions among a) FOPs, b) other marketing components on the package, and c) time pressure. |

Liking, Satisfaction, and Label Preference |

Conclusion: Consistent with 2016 RTI Addendum, results from these recent studies reveal that despite some varied preferences, consumers prefer simple labels, such as the ones using a summary system (e.g., SENS). |

Understanding

|

Conclusion: The updated literature review confirms the 2016 RTI findings. Studies indicate FOPs in general can help consumers to understand nutrition information, but to different extents and suggests that the more simplified FOPs are easier for consumers to understand. |

Effects on Use and Likely Purchase Behavior |

Conclusion: Studies suggest that FOP nutrition symbols lead to mock ‘purchase’ of foods with better overall nutrition profiles, but results appear to be mixed on experimental and self-assessed purchase intentions; some studies showed significant FOP effects and others did not. |

Effects on Sales (Purchases) and Consumption |

Conclusion: The studies suggest that implementation of FOP Nutrition symbols has led to product reformulations and there is some evidence of increases in sales of products bearing a FOP symbol. |

Effects on Educational Differences |

Conclusion: Although one study found differences in response to food labels by nutrition knowledge and motivation to eat healthfully, education-level was not revealed to be a significant factor in consumers’ differentiating of FOP labels. |

Effects on Diverse Populations |

Conclusion: While results from the studies varied, they point toward positive comprehension effects of FOP nutrition information for low-income children. |

Evaluation of Government FOP Nutrition Symbols |

Conclusion: These studies highlighted the potential benefits of having a government-created symbol. |

In January 2019, the World Cancer Research Fund released a report entitled “Building momentum: lessons on implementing a robust front-of-pack food label” that focuses on instructions for government implementation of FOP nutrition labels. Authors conducted a literature review on challenges to international, government implemented nutrition labels and interviewed 23 international policymakers, academics, advocates. With a focus on interpretive FOP labels –which they prefer over nutrient-specific systems - the report contains recommendations for the development, design, implementation, defense, monitoring and evaluation of the FOP. The report recommends governments institute mandatory FOP labels to overcome limited industry uptake but acknowledged that voluntary labels will also help to achieve public health goals by adhering to a process starting with clear policy objectives, knowledge of the legal context, cultivating partners and stakeholders, implementing well-designed public education, and evaluating the labels’ effectiveness post implementation. The report cited challenges to government FOP label implementation - specifically tactics to delay, divide, deflect, and deny.

Additionally, in 2019 the World Health Organization (WHO) released a manual entitled, “WHO guiding principles and framework manual for front-of-pack labelling for promoting healthy diets”. The document is meant to support countries in the development, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of an appropriate FOP system to help improve dietary patterns and reduce the burden of diet-related noncommunicable diseases. The five overarching guiding principles for FOP that form the basis of the manual are as follows:

Principle 1: The FOP system should be aligned with national public health and nutrition policies and food regulations, as well as with relevant WHO guidance and Codex guidelines.

Principle 2: A single system should be developed to improve the impact of the FOP system.

Principle 3: Mandatory nutrient declarations on food packages are a prerequisite for FOP systems.

Principle 4: A monitoring and review process should be developed as part of the overall FOP system for continuing improvements or adjustments, as required.

Principle 5: The aims, scope, and principles of the FOP system should be transparent and easily accessible

Results of Key Systematic Reviews (2018 - 2021)

Mirroring methods discussed in the previous section, FDA further reviewed the literature, beginning where the last review, conducted August 2016 - October 2018, was completed. The review in this section covers the scientific literature on FOP from November 2018 to August 2021, using the same targeted database search algorithm and the analytical categories used in earlier reviews. We analyzed one hundred and eight additional scientific articles on FOP for this update. Table 2 below presents the highlights and conclusions of this review by analytical category.

Table 2. Highlights and Conclusions of updated FOP nutrition labeling literature by analytical category (November 2018 – August 2021)

Analytical Category |

Highlights and conclusions |

Attention and Processing |

Conclusion: These studies extend the findings of the 2016 RTI Addendum, which found that FOP labels catch consumers’ attention. Additionally, one of the studies (Deliza, 2019) suggests that over time, as consumers become more familiar with FOP labels, they will become even more useful. |

Liking, Satisfaction, and Label Preference |

Conclusion: Results from these recent studies reveal that additional research should be conducted to determine which type of FOP is preferred by most U.S. consumers. However, based on these findings, it appears consumers prefer simple, color labels, such as the ones using a summary system (i.e., Multiple Traffic Light symbols). |

Understanding

|

Conclusion: The updated literature review confirms the 2016 RTI findings. The adoption and implementation of a uniform FOP labeling system could be beneficial to consumers at the point of purchase, help consumers better understand nutrition information, and therefore could help consumers improve their diet quality leading to a reduction in the incidence of diet-related chronic diseases. The updated literature review also further supports the conclusions of FDA’s previous updated literature review that the summary/interpretive systems are likely to be more effective than purely informative systems in helping consumers understand the total nutritional quality of foods. |

Effects on Use & Likely Purchase Behavior |

Conclusion: These recent studies suggest that FOP labels are effective at helping consumers identify products with higher nutritional quality and also may be effective at positively impacting consumers’ intent to purchase healthful foods. |

Effects on Sales (Purchases) and Consumption |

Conclusion: These findings suggest that FOPs can influence healthier food purchases in supermarkets and, with prolonged use, may lead to improved health outcomes. |

Effects on Educational Differences |

Conclusion: Both studies found that interpretive FOP schemes, versus a “no FOP” condition, helped all consumers, regardless of education or health literacy levels, to correctly assess a food’s healthfulness even if some differences between higher and lower education and health literacy were found. |

Effects on Diverse Populations (Income, Age, Race/Ethnicity, Minority) |

Conclusion: While results from the studies varied, they point toward positive effects of FOP labels on consumers’ ability to select healthier products among diverse populations. |

Evaluation of Government-Instituted FOP Nutrition Labeling Systems |

Conclusion: These studies highlighted the potential benefits of having a government-created and sponsored FOP labeling scheme for assisting consumer food choices. |

Results of Key Systematic Reviews (2021 - 2022)

FDA further updated the 2018-2021 FOP literature review by reviewing the scientific literature on FOP from January 2021 to August 2022, using a slightly modified version of the targeted database search algorithm but the same analytical categories used in earlier reviews. Because of the proliferation in FOP schemes worldwide since the earlier iterations of this literature review, we included the names of the schemes to the targeted database search algorithms that were used in the 2016-2020 reviews (See highlighted text in Appendix B). We analyzed 77 scientific articles on FOP in the January 2021 to August 2022 FOP literature review update. Table 3 below presents the highlights and conclusions of this literature review by analytical category.

Table 3. Highlights and conclusions of updated FOP nutrition labeling literature by analytical category (January 2021 – August 2022)

Analytical Category |

Highlights and conclusions |

Attention and Processing |

Conclusion: These studies extend previous findings, which found that FOP labels – particularly those utilizing color – catch consumers’ attention. Also, in keeping with the prior reviews, these studies suggest that familiarity with FOP labels will make them even more useful. |

Liking, Satisfaction, and Label Preference |

Conclusion: These current findings reinforce the earlier finding that consumers prefer labels that convey a clear message. However, as with previous reviews, results from these recent studies reveal that the literature is not conclusive about consumer preferences on FOP schemes. |

Understanding

|

Conclusion: The updated literature review confirms earlier findings and demonstrates that since most FOP labels help consumers understand nutrition quality of a food, the adoption and implementation of a uniform FOP labeling system could be beneficial to consumers. |

Effects on Use & Likely Purchase Behavior |

Conclusion: These recent studies suggest that FOP schemes can be effective at helping consumers identify products with higher nutritional quality and can positively impact consumers’ intent to purchase healthful foods, with varying results. |

Effects on Sales (Purchases) and Consumption |

Conclusion: These findings suggest that simplified, summary, colorful FOP schemes can encourage healthier purchases in supermarkets but that more research is needed to demonstrate the ability of FOP schemes with regard to overall health and diet-related chronic disease outcomes. |

Effects on Educational Differences |

Conclusion: These studies highlight the importance of specific FOP labeling education in order to help consumers make informed, healthier choices. |

Effects on Diverse Populations |

Conclusion: While results from the studies varied as in previous reviews, they continue to show generally positive effects of FOP labels on the ability of different populations to select healthier products. Of particular importance are findings on the influence of color and design in helping to inform purchasing decisions of these populations. |

Evaluation of Government-Instituted FOP Nutrition Symbols |

Conclusion: These studies highlighted the potential benefits of having a government created and mandated FOP labeling system for assisting consumer food choices. |

Appendix A: Front of Pack Nutrition Labeling Schemes and Symbols Available Online and in the Scientific Literature in 2018.

Appendix B: Methods Report for Systematic Review of Literature on FOP Labeling Including Study Protocol

Introduction

FDA updated the 2016 FOP literature review by reviewing the scientific literature on FOP labeling in four stages. The Phase I literature search covered August 2016 to the end of March 2018. The Phase II search covered the literature from April 2018 to October 2018. The Phase III search covered literature from November 2018 to August 2021. The Phase IV search covered literature from January 2021 to August 2022, in order to capture literature published in early 2021 that may not have been included in databases at the time of the Phase III search. The first three stages used the same targeted database search algorithm and the analytical categories used in the earlier literature reviews for which this project is a follow-on. For the Phase IV search, the database search algorithm was expanded to include the names of the FOP labeling systems identified in the previous three stages.

Objective

Conduct a systematic review of the literature on front of package nutrition labeling/systems/frameworks/symbols/icons since August 2021, using the same search algorithm that had been used for the Hersey, et al (2013), RTI Addendum (2016), and FDA (2021) reviews.

Methods

Articles in English meeting the search criteria and time frame constraints (January 2021 to present for the Phase IV search) were eligible for inclusion in the literature search.

Search Strategy

We searched the following databases: PubMed, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, under which the following databases are subsumed: CHINAHL, Business Source Corporate, PsycINFO, AGRICOLA, Food Science and Technology Abstracts, New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Report, NTIS, AgEcon, and CAB Abstracts. The databases Web of Science, CAB Abstracts and New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Report, none of which had results in the Phase II or III searches, were not searched in Phase IV.

The following are the search terms used for each database identified above, with the additional terms used in Phase IV indicated by bold type, as well as the number of results returned by database. The first number on the “Results” line is from the Phase I search; the second number, the one in parentheses, is the number returned for the Phase II search; the third number, the one in brackets, is the number returned for the Phase III search, and the fourth number, the one in curly brackets, is the number returned for the Phase IV search. The total number of articles returned in Phases I, II, III and IV searches include many duplicates that were identified and deleted before researchers began the review.

PubMed

Results = 66 (18) [148] {152}

((("front of package nutrition label" OR "front of package nutrition labels" OR "front of pack nutrition label" OR "front of pack nutrition labels" OR "FOP label" OR "FOP labels" OR "front of package label" OR "front of package labels" OR “shelf-labeling” OR "shelf labeling" OR "shelf nutrition label" OR "shelf nutrition labels") AND (consumer OR "consumer behavior" OR "consumer behaviors" OR "consumer preference" OR "consumer preferences" OR "consumer satisfaction" OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers)) AND ("2021"[Date - Publication] : "3000"[Date - Publication])) OR (("Health Star" OR "Traffic Light*" OR "Reference Intakes" OR "Warning symbol" OR "Heart-check" OR "Healthier Choice Symbol" OR "Nutri-Score" OR "Nutri score" OR Nutri-Score OR NuVal) AND label* AND (consumer OR "consumer behavior" OR "consumer behaviors" OR "consumer preference" OR "consumer preferences" OR "consumer satisfaction" OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers) AND ("2021"[Date - Publication] : "3000"[Date - Publication])))

Web of Science

Results = 22 (0) [0]

(TS=("front of package nutrition label" OR "front of package nutrition labels" OR "front of pack nutrition label" OR "front of pack nutrition labels" OR "FOP label" OR "FOP labels" OR "front of package label" OR "front of package labels" OR "shelf-labeling" OR "shelf labeling" OR “shelf nutrition label” OR “shelf nutrition labels”) AND TS=(consumer OR consumers OR “consumer behavior” OR “consumer behaviors” OR “consumer preference” OR “consumer preferences” OR “consumer satisfaction” OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers))

Science Direct

Results = 0 (advanced search) (3) [39] {45}

Title-Abstr-Key ("front of pack* nutrition label*" OR "FOP label*" OR "front of package label*" OR “shelf labeling” OR “shelf nutrition label*”) AND Title-Abstr-Key (consumer* OR effective OR design* OR nutrition OR producer* OR retailer*) date: 2016-2018

Phase IV search information: Science Direct limits the number of Boolean operators that can be used in any one field at a time to no more than 8. Science Direct also does not support truncation. As a result, searches were conducted as follows:

Title, abstract, keywords: ("front of pack nutrition label" OR "front of package nutrition label" OR "front of pack nutrition labeling" OR "front of package nutrition labeling" OR "front of pack label" OR "front of pack labeling" OR "front of package label" OR "front of package labeling" OR "FOP label") Year: 2021-2022

Title, abstract, keywords: ("front of pack nutrition labels" OR "front of package nutrition labels" OR "front of pack labels" OR "front of package labels" OR "FOP labels" OR “FOP labeling”) Year: 2021-2022

Title, abstract, keywords: ("shelf label" OR "shelf labels" OR "shelf labeling" OR "shelf nutrition label" OR "shelf nutrition labels" OR "shelf nutrition labeling") AND (nutrition OR design OR effective) Year: 2021-2022

Title, abstract, keywords: ("shelf label" OR "shelf labels" OR "shelf labeling" OR "shelf nutrition label" OR "shelf nutrition labels" OR "shelf nutrition labeling") AND (consumer OR retailer OR producer) Year: 2021-2022

Title, abstract, keywords: ("Health Star" OR "Traffic Light" OR "Reference Intakes" OR "Warning symbol" OR "Heart-Check" OR "Healthier Choice Symbol") AND (label OR labels OR labeling) Year: 2021-2022

Title, abstract, keywords: ( "Nutri-Score" OR "Nutri score" OR Nutri-Score OR NuVal) AND (label OR labels OR labeling) Year: 2021-2022

Food Science and Technology Abstracts

Results = 13 (2) [0] {99}

((("front of package nutrition label" OR "front of package nutrition labels" OR "front of pack nutrition label" OR "front of pack nutrition labels" OR "FOP label" OR "FOP labels" OR "front of package label" OR "front of package labels" OR shelf-labeling OR "shelf labeling" OR "shelf nutrition label" OR "shelf nutrition labels") AND (consumer OR consumers OR "consumer behavior" OR "consumer behaviors" OR "consumer preference" OR "consumer preferences" OR "consumer satisfaction" OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers)) OR (("Health Star" OR "Traffic Light*" OR "Reference Intakes" OR "Warning symbol" OR "Heart-check" OR "Healthier Choice Symbol" OR "Nutri-Score" OR "Nutri score" OR Nutri-Score OR NuVal) AND label* AND (consumer OR consumers OR "consumer behavior" OR "consumer behaviors" OR "consumer preference" OR "consumer preferences" OR "consumer satisfaction" OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers))) AND (pd(20210101-20221231)

CINAHL

Results = 15 (1) [0] {96}

((("front of package nutrition label" OR "front of package nutrition labels" OR "front of pack nutrition label" OR "front of pack nutrition labels" OR "FOP label" OR "FOP labels" OR "front of package label" OR "front of package labels" OR "shelf-labeling" OR "shelf labeling" OR “shelf nutrition label” OR “shelf nutrition labels”) ) AND ( consumer OR consumers OR “consumer behavior” OR “consumer behaviors” OR “consumer preference” OR “consumer preferences” OR “consumer satisfaction” OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers ) AND (Limiters - Published Date: 20210101-20221231; English Language)) OR (("Health Star" OR "Traffic Light*" OR "Reference Intakes" OR "Warning symbol" OR "Heart-check" OR "Healthier Choice Symbol" OR "Nutri-Score" OR "Nutri score" OR Nutri-Score OR NuVal) AND label* AND (consumer OR "consumer behavior" OR "consumer behaviors" OR "consumer preference" OR "consumer preferences" OR "consumer satisfaction" OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers) AND (Limiters - Published Date: 20210101-20221231; English Language)))

PsycInfo

Results = 7 (0) [0] {21}

(noft(("front of package nutrition label" OR "front of package nutrition labels" OR "front of pack nutrition label" OR "front of pack nutrition labels" OR "FOP label" OR "FOP labels" OR "front of package label" OR "front of package labels" OR "shelf-labeling" OR "shelf labeling" OR “shelf nutrition label” OR “shelf nutrition labels” ) AND ( consumer OR consumers OR “consumer behavior” OR “consumer behaviors” OR “consumer preference” OR “consumer preferences” OR “consumer satisfaction” OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers))) OR (noft(("Health Star" OR "Traffic Light*" OR "Reference Intakes" OR "Warning symbol" OR "Heart-check" OR "Healthier Choice Symbol" OR "Nutri-Score" OR "Nutri score" OR Nutri-Score OR NuVal) AND label* AND (consumer OR "consumer behavior" OR "consumer behaviors" OR "consumer preference" OR "consumer preferences" OR "consumer satisfaction" OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers))) AND pd(2021-2022)

Business Source Complete

Results = 8 (2) [0] {32}

((("front of package nutrition label" OR "front of package nutrition labels" OR "front of pack nutrition label" OR "front of pack nutrition labels" OR "FOP label" OR "FOP labels" OR "front of package label" OR "front of package labels" OR "shelf-labeling" OR "shelf labeling" OR “shelf nutrition label” OR “shelf nutrition labels”) ) AND ( consumer OR consumers OR “consumer behavior” OR “consumer behaviors” OR “consumer preference” OR “consumer preferences” OR “consumer satisfaction” OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers) AND (Limiters - Published Date: 20210101-20221231: English language)) OR (("Health Star" OR "Traffic Light*" OR "Reference Intakes" OR "Warning symbol" OR "Heart-check" OR "Healthier Choice Symbol" OR "Nutri-Score" OR "Nutri score" OR Nutri-Score OR NuVal) AND label* AND (consumer OR "consumer behavior" OR "consumer behaviors" OR "consumer preference" OR "consumer preferences" OR "consumer satisfaction" OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers) AND (Limiters - Published Date: 20210101-20221231; English Language)))

AGRICOLA (Dialog Proquest)

Results = 5 (1) [0] {71}

((ab,ti(("front of package nutrition label" OR "front of package nutrition labels" OR "front of pack nutrition label" OR "front of pack nutrition labels" OR "FOP label" OR "FOP labels" OR "front of package label" OR "front of package labels" OR "shelf-labeling" OR "shelf labeling" OR “shelf nutrition label” OR “shelf nutrition labels”) AND (consumer OR consumers OR “consumer behavior” OR “consumer behaviors” OR “consumer preference” OR “consumer preferences” OR “consumer satisfaction” OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers)) AND (Limited by: Date: From 2021 to August 2022; Language:English)) OR (ab,ti(("Health Star" OR "Traffic Light*" OR "Reference Intakes" OR "Warning symbol" OR "Heart-check" OR "Healthier Choice Symbol" OR "Nutri-Score" OR "Nutri score" OR Nutri-Score OR NuVal) AND label* AND (consumer OR "consumer behavior" OR "consumer behaviors" OR "consumer preference" OR "consumer preferences" OR "consumer satisfaction" OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers) AND (Limited by: Date: From 2021 to August 2022; Language:English))) AND (all(label*))

Cab Abstracts (via ProQuest Dialog)

Results = 14 (0) [0]

("front of package nutrition label" OR "front of package nutrition labels" OR "front of pack nutrition label" OR "front of pack nutrition labels" OR "FOP label" OR "FOP labels" OR "front of package label" OR "front of package labels" OR "shelf-labeling" OR "shelf labeling" OR “shelf nutrition label” OR “shelf nutrition labels”) AND (consumer OR consumers OR “consumer behavior” OR “consumer behaviors” OR “consumer preference” OR “consumer preferences” OR “consumer satisfaction” OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers)

AgEcon

Results = 18 (0) [0] {3}

Search filter = any field / (date added/modified 01/04/2016 to 31/12/2018)

Results total = 51 (0) removal of duplicates = 33; [1]

front of pack* nutrition label* = 15 (1=2016); [1]

FOP label* = 6 (none 2016-) [0]

front of package label* = 8 (none 2016-) [1, duplicate]

shelf labeling = 8 (only 1=2017) [0]

shelf nutrition label* = 14 (1=2016; 3=2017) [0]

("front of package nutrition label" OR "front of package nutrition labels" OR "front of pack nutrition label" OR "front of pack nutrition labels" OR "FOP label" OR "FOP labels" OR "front of package label" OR "front of package labels" OR shelf-labeling OR "shelf labeling" OR "shelf nutrition label" OR "shelf nutrition labels") AND (consumer OR "consumer behavior" OR "consumer behaviors" OR "consumer preference" OR "consumer preferences" OR "consumer satisfaction" OR "consumer response" OR "consumer responses" OR effective OR design OR designs OR nutrition OR producer OR producers OR retailer OR retailers) AND year:2021->2022

"Health Star" AND year:2021->2022

"Traffic Light*" AND year:2021->2022

"Reference Intakes" AND year:2021->2022

"Warning symbol" AND year:2021->2022

“Heart-check” AND year:2021->2022

"Healthier Choice Symbol" AND year:2021->2022

“Nutri-Score” AND year:2021->2022

"Nutri score" AND year:2021->2022

Nutri-Score AND year:2021->2022

NuVal AND year:2021->2022

NTIS

Results = {0}

No search terms provided for Phase I, II or III. For Phase IV, each labeling term listed below was searched individually. The consumer terms were not used, so as not to limit the search results.

"front of package nutrition label"

"front of package nutrition labels"

"front of pack nutrition label"

"front of pack nutrition labels"

"FOP label"

"FOP labels"

"front of package label"

"front of package labels"

shelf-labeling

"shelf labeling"

"shelf nutrition label"

"shelf nutrition labels"

"Health Star"

"Traffic Light*"

"Reference Intakes"

"Warning symbol"

“Heart-check”

"Healthier Choice Symbol"

“Nutri-Score”

"Nutri score"

Nutri-Score

NuVal

Phase I (Search period: August 2016 – March 2018)

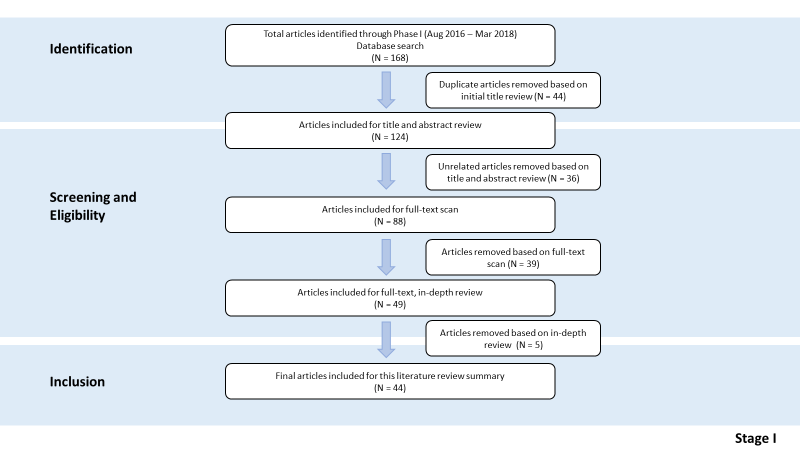

Overall, 168 articles were identified in the literature search; 44 duplicates were removed; 36 articles were removed because they were not related to the research topic; 39 additional articles were removed because, 1) upon closer examination they were not related to the research topic, 2) they were already reported in one of the previous literature reviews, or 3) they were duplicates of articles in the review; five articles were removed at the final stage, after the in-depth review because they were determined by both researchers that they were not relevant to the research topic. 44 articles from this stage of search were included in this literature review summary.

Phase II (Search period: April 2018 – October 2018)

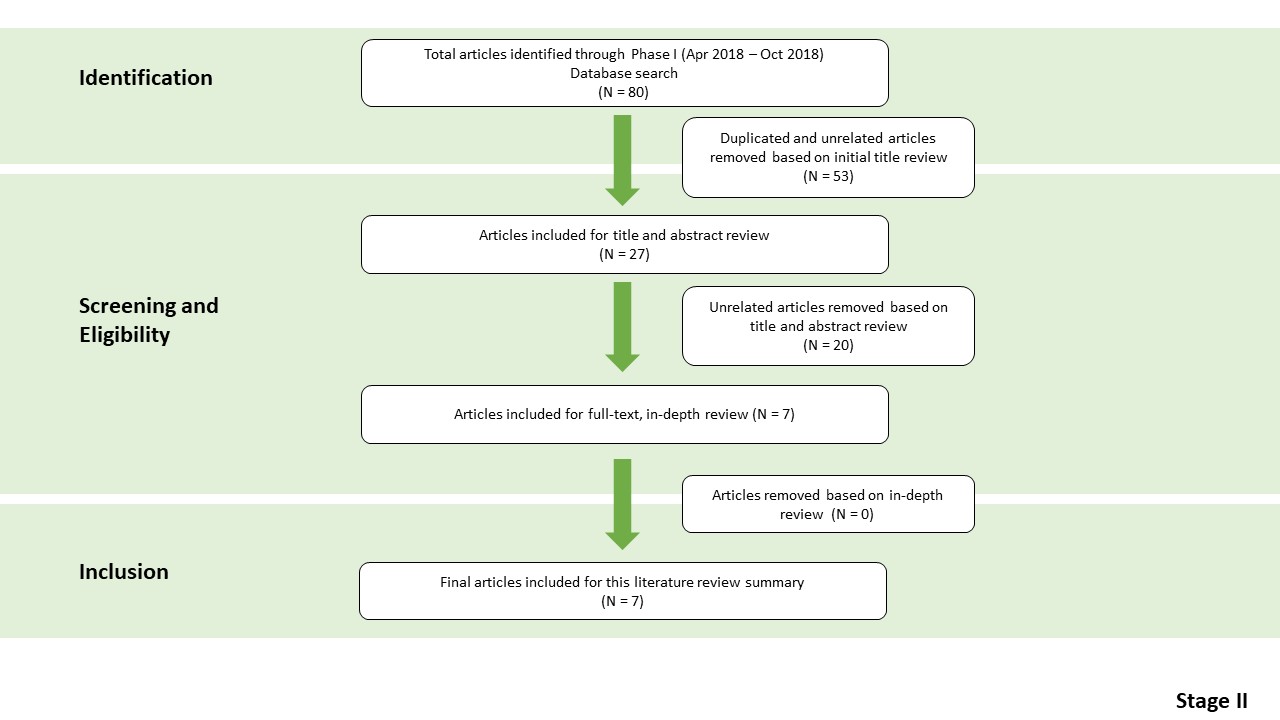

Overall, 80 articles were identified in the literature search; 53 duplicates were removed; 20 articles were further removed because they were not related to the research topic. Seven articles from this stage of search were included in this literature review summary.

Phase III (Search period: November 2018 to August 2021)

Overall, 187 articles were identified in the literature search; 12 duplicates were removed; 66 articles were further removed because they were not related to the research topic. One article was removed because it was not published in English. One hundred and eight articles from this stage of search were included in this literature review summary.

Phase IV (Search period: January 2021 to August 2022)

Overall, 517 articles were identified in the literature search, to which 40 articles were added from FDA’s Web of Science updates, resulting in 557 articles. Of those, 46 articles included in Phase III were removed as well as 224 duplicates and 15 citations for which no publication existed; 200 articles were further removed because they were not related to the research topic (178 removed based on title and abstract review; 22 removed following full text review). Seventy-two articles from this stage of search were included in this literature review summary.

Identification |

Duplicate

articles removed based on (1) previous literature review and (2)

initial title review (N=274); Citations without publication

removed (N = 15)

Total

number of articles identified through Phase IV search (January

2021 – August 2022) plus FDA Web of Science alerts (N

= 557) |

|

|

Screening and Eligibility |

Unrelated

articles removed based full text scan (N=22)

Unrelated

articles removed based on title and abstract review (N=178)

Articles

included for full-text scan (N

= 94)

Articles

included for abstract and title review (N

= 272) |

|

|

Inclusion |

Final

articles included for this literature review summary (N

= 72) |

Stage IV

Mechanism Used to Manage the Review

Search results were downloaded to- and delivered in- EndNote (20.4.1, Bld 16297), a reference management software program supported by FDA’s reference library.

Selection Process

Researchers imported basic information for each of the 94 identified articles identified in Phase IV into Excel, into a file that listed author, year, title, study type, method, sample size, type of FOP, FOP image, country, highlight of findings, and whether the study included “education” as a variable. The articles were divided evenly among five researchers who read them and sorted them into the summary categories that had been used by the prior studies: Attention and processing; Liking, satisfaction, and label preference; Understanding, Effects on use and likely purchase; Effects on sales (purchases and consumption); Effects on Diverse Populations; and Evaluation of Government FOP Nutrition Symbols. At the request of the HSIT, we added a category for Effects on Educational Differences. Researchers also wrote a summary of each article’s findings. These summaries were used to develop overall conclusions by category. The Phase IV reviews were completed by one researcher, who sorted the articles into the same categories used in Phase III and summarized the articles’ findings.

Appendix C: Summary of Articles Included in FDA Healthy Symbol Literature Review (2016 to 2022)

Author |

Title |

Year |

Method |

FOP |

FOP Image |

Country |

Highlights of Findings |

Brown, et al. |

The influence of front-of-pack nutrition information on consumers' portion size perceptions |

2017 |

Quantitative.

n=117 |

|

None provided |

Australia |

|

Cook and Kizilova |

Direct and Indirect Processing Effects of Front-of-Package Labels |

2017 |

Quantitative. Online study: comparative setting to measure differences in label formats between four cans of beef stew on a grocery shelf. 2 FOP Label Modality [evaluative (symbol-based) or objective (text- based)] × 3 Information Processing [immediate (control), elaboration, or distraction] n=311 |

|

None provided |

US |

|

De la Cruz- Gongora, et al. |

Understanding and acceptability by Hispanic consumers of four front-of-pack food labels |

2017 |

Qualitative.

n=135 parents of 5th grade students |

|

|

Mexico |

the nutritional knowledge and time needed for interpretation

FOP that allows easily identification of healthy products while considering food purchasing time limitations and interpretation of food portions. |

Dukeshire and Nicks |

Benchmarks and Blinders: How Canadian Women Utilize the Nutrition Facts Table |

2017 |

Qualitative. Open-ended interviews on how females (45 min) use the NFT(Nutrition Fact Table) in their everyday shopping decisions and food consumption habits. Participants were provided with 2 cereal food packages with NFTs to assist in their responses. n=13 |

|

N/A |

Canada |

|

Dunford, et al. |

Color-Coded Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels - An Option for US Packaged Foods? |

2017 |

Quantitative. Categorized product labels n=175,198 products |

Traffic Light |

N/A |

US |

>40% of US packaged foods would receive the "red" light for sodium, total fat, and total sugars based on their algorithm for 'healthy'. >50% received a red light for total fat and sodium. Only 30% of products were considered "healthy' using the traffic light aggregate score method. |

Dunford, et al. |

A comparison of the Health Star Rating system when used for restaurant fast foods and packaged foods |

2017 |

Quantitative. Nutrient content data for fast food menu items were collected from the websites of 13 large Australian fast-food chains. Scored 1529 fast food products and 3810 packaged food products for the "Health Star Rating." Statistics describing HSR values for fast foods were calculated and compared to results for comparable packaged foods. n=1529 fast food products and 3810 packaged food products |

Health Star Rating (HSR) |

N/A |

Australia |

|

Author |

Title |

Year |

Method |

FOP |

FOP Image |

Country |

Highlights of Findings |

Fernan, et al. |

Health Halo Effects from Product Titles and Nutrient Content Claims in the Context of "Protein" Bars |

2017 |

Quantitative. Between Subjects Experiment n=274 |

Traffic Light |

|

USA |

Product title (e.g., Protein Bar") had a greater effect on measures of product healthfulness than did the traffic light symbol. |

Georgina-Russell, et al. |

The impact of front-of-pack marketing attributes versus nutrition and health information on parents' food choices |

2017 |

Quantitative. Discrete choice experiment n=520 parents |

Health Star Rating (HSR) |

|

Australia |

Parents preferred cereal with 5 stars and least preferred cereal with 2 stars, but the color of the cereal made the biggest impact on preference (because they really didn't like the colorful flakes!) "The present findings indicate that in order to shift parents ‘packaged food choices towards healthier alternatives, which is the aim of government-initiated FOP health and nutrition labeling systems, consideration needs to be given to not only the impact of such systems in isolation, but their effects when they co-occur with marketing attributes..." |

Graham, et al. |

Impact of explained v. unexplained front- of-package nutrition labels on parent and child food choices: a randomized trial |

2017 |

Quantitative. Experimental study n=153 parent/child pairs |

|

N/A |

USA |

Study found virtually no effect of either type of FOP label on selecting of more healthful product. Found some modest effects of in-aisle explanatory signage. |

Hobin, et al. |

Consumers' Response to an ONutri-Scorehelf Nutrition Labelling System in Supermarkets: Evidence to Inform Policy and Practice |

2017 |

Quantitative. Quasi-experiment and "exit" survey

|

Guiding Stars |

|

Canada |

Relative to control supermarkets, shoppers in intervention supermarkets made small but significant shifts toward purchasing foods with higher nutritional ratings; however, shifts varied in direction and magnitude across food categories. These shifts translated into foods being purchased with slightly less trans fat and sugar and more fiber and omega-3 fatty acids. We also found increases in the number of products per transaction, price per product purchased, and total revenues. Exit survey results show a modest proportion of consumers were aware of, understood, and trusted Guiding Stars in intervention supermarkets, and a small proportion of consumers reported using this system when making purchasing decisions. However, 47% of shoppers exposed to Guiding Stars were confused when asked to interpret the meaning of a 0-star product that does not display a rating on the shelf tag. |

Julia, et al. |

Perception of different formats of front- of-pack nutrition labels according to sociodemographic, lifestyle and dietary factors in a French population: cross- sectional study among the NutriNet- Sante cohort participants |

2017 |

Quantitative. Cross sectional web-based survey n=21,702 |

|

|

France |

|

Machin, et al. |

Consumer Perception of the Healthfulness of Ultra-processed Products Featuring Different Front-of- Pack Nutrition Labeling Schemes |

2017 |

Quantitative.

n=300 |

|

|

Uruguay |

|

Author |

Title |

Year |

Method |

FOP |

FOP Image |

Country |

Highlights of Findings |

Mhurchu, et al. |

Effects of a Voluntary Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling System on Packaged Food Reformulation: The Health Star Rating System in New Zealand |

2017 |

Quantitative. Observational study of the composition of packaged foods before and after the introduction of the HSR system in New Zealand. Homescan® data were obtained for 1. 2014 (n = 1726 households and 4.65 million products); 2. 2015 (n = 1827 households, 4.89 million products); and 3. 2016 (n = 1839 households, 4.89 million products). |

Health Star Rating |

|

New Zealand |

Two years following adoption of the voluntary front-of-pack Health Star Rating System in New Zealand, approximately 5% of packaged food and non-alcoholic beverage products displayed HSR star graphic labels. Food groups with the highest rates of uptake of HSR labels were cereals, convenience foods, packaged fruit and vegetables, sauces and spreads, and ‘other’ products (predominantly breakfast beverages).

The majority of products displaying HSR labels had star ratings greater than 3.0, and the median rating was 4.0. Products displaying HSR star graphic labels had significantly lower mean saturated fat, total sugar and sodium contents, and higher fibre content, compared to non- HSR products. Approximately eight in 10 products (83%) displaying HSR graphics had been reformulated to some extent, and small but significant favourable changes were observed in mean energy, sodium and fibre contents, compared with product composition prior to adoption of HSR. |

Neal, et al. |

Effects of Different Types of Front-of-Pack Labelling Information on the Healthiness of Food Purchases-A Randomised Controlled Trial |

2017 |

Quantitative. In store experimental study comparing four FOP labeling schemes and the Nutrition Information Panel (NIP) using a Smartphone app in the store. The main outcome was the mean nutrient profile score for all food and beverages purchased over the four-week intervention period. n=1,578 participants |

5. Nutrition Information Panel |

|

Australia |

These data provide endorsement of the Australian Government’s decision to adopt the HSR as their recommended front-of-pack labelling system. The HSR was as good as any other label that was tested in terms of the healthiness of purchased foods, while being superior to others in several aspects of consumer preference. It was also a front runner in terms of its utility across groups with a range of different levels of nutritional knowledge. This is an important attribute given the greater burden of diet-related ill health amongst less educated sectors of the population and the known difficulties that some groups have in understating nutrition information. |

Ning, et al. |

Dietary sodium reduction in New Zealand: influence of the Tick label |

2017 |

Quantitative. Product examination (n=56) and semi-structured interviews (n=5) |

Tick |

N/A |

New Zealand |

Evidence of product reformulation (sodium-reduction) in "Tick- approved" products. |

Pettigrew, et al. |

The types and aspects of front-of-pack food labelling schemes preferred by adults and children |

2017 |

Quantitative. 1. cross-sectional online survey of 2058 Australian consumers (1558 adults and 500 children) assessed preferences b/w a daily intake FOP, a traffic light FOP, and the Health Star Rating FOP. N=2058 (included adults & children) |

1.Daily Intake 2. Traffic Light 3.Health Star Rating (HSR) |

|

Australia |

|

Raine, et al. |

Policy recommendations for front-of- package, shelf, and menu labelling in Canada: Moving towards consensus |

2017 |

Consensus Conference (Global Recommendations) |

N/A |

N/A |

Canada |

Experts and professionals in Nutrition recommend standardizing FOP with an interpretive logo that distills meaning and utilizes a graduated scale to represent nutritional guidance. |

Roseman, et al. |

Attitude and Behavior Factors Associated with Front-of-Package Label Use with Label Users Making Accurate Product Nutrition Assessments |

2017 |

Quantitative.

Extended, a binary symbol, and no-label control

|

|

|

United States |

frequency of selecting food for healthful reasons were associated with FOP label use (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively).

|

Author |

Title |

Year |

Method |

FOP |

FOP Image |

Country |

Highlights of Findings |

Sanjari, et al. |

Dual-process theory and consumer response to front-of-package nutrition label formats |

2017 |

Quantitative. Systematic literature review n=59 published papers |

N/A |

N/A |

Germany |

situations? Consumers' processing mode (system 1 - quick/automatic VS. system 2 - slow/deliberate) varies both within and between people and impacts effectiveness of a variety of FOP labels. Consumer's preferences vary.

|

Sanjari, et al. |

Choosing Fast and Slow: Processing Mode and Consumer Response to FOP Nutrition Label Formats |

2017 |

Quantitative. Online experimental study: 2 (label format) X 2 (motivation: targeted, nontargeted). Mock pizza products. N=155 (Americans) |

|

N/A |

Germany |

FOP labels are used differently depending on nutrition knowledge and time pressure. One Study found that processing mode mediates the impact of FOP label usage on making healthy choices. Intuitive versus deliberate mode… 2nd study found that time pressure and nutrition knowledge interact on processing mode.

*This is a conference proceeding |

Talati, et al. |

The impact of interpretive and reductive front-of-pack labels on food choice and willingness to pay |

2017 |

Quantitative. Discrete choice experiment; willingness to pay n=2069 |

|

|

Australia |

Interpretive FOPs with a summary indicator are more effective than reductive FOPs in facilitating healthier choices. |

Talati, et al. |

Consumers' responses to health claims in the context of other on-pack nutrition information: a systematic review |

2017 |

Quantitative. Meta-analyses n=24 |

Traffic lights |

|

Australia |

Meta analyses was not symbol focused, but they found that traffic light symbols worked better than the NFL for helping participants correctly identify healthy and unhealthy products. |

Yoo, et al. |

Children and adolescents' attitudes towards sugar reduction in dairy products |

2017 |

Quantitative. Cross-sectional survey - convenience sample (although the article says experimental design) n=646 |

Variety of traffic light symbols |

|

Uruguay |

Compared the effects of a sugar claim modulated by the presence of a traffic light symbol. Both 'claim types' increased understanding of product healthfulness but the traffic lights did not affect liking of the product. |

Acton and Hammond |

The impact of price and nutrition labelling on sugary drink purchases: Results from an experimental marketplace study |

2018 |

Quantitative.

n=675 |

|

|

Canada |

|

Acton, et al. |

Consumer perceptions of specific design characteristics for front-of-package nutrition labels |

2018 |

Quantitative.

|

Health warning |

|

Canada |

|

Author |

Title |

Year |

Method |

FOP |

FOP Image |

Country |

Highlights of Findings |

Carter and Gonzalez-Vallejo |

Nutrient-specific system versus full fact panel: Testing the benefits of nutrient- specific front-of-package labels in a student sample |

2018 |

Quantitative. 1. To evaluate and assess nutrition judgement accuracy by comparing nutrition judgements to a nutrition expert criterion (NuVal) in three package conditions:

|

Nutrition Keys Label (based on the General Mills nutrient-specific FOP label) - (DV%?) |

|

US |

Labels that included FOP information that was relevant to the overall nutritional quality of the product did not result in greater nutritional accuracy compared to an FOP with irrelevant information, or no FOP label at all.

Author's discussion: "the practical utility of nutrient-specific labels for improving nutritional judgment is likely negligible". |

Finkelstein, et al. |

Identifying the effect of shelf nutrition labels on consumer purchases: results of a natural experiment and consumer survey |

2018 |

Quantitative. Sales data evaluation and online convenience sample survey n=665 |

NuVal |

N/A |

|

Researchers evaluated the change in sales when NuVal changed its algorithm for scoring the nutritional quality of foods. When scores decreased, sales also decreased, but they couldn’t control for anything except price -which had not changed. 44% noticed the NuVal label & 32% knew what the scores were about and the meaning of the scores. A very small fraction reported using the scores to influence purchases. |

Gorski-Findling, et al. |

Comparing five front-of-pack nutrition labels' influence on consumers' perceptions and purchase intentions |

2018 |

Quantitative. Experimental Study n=1247 |

|

|

USA |

DV= purchase intent, accuracy of interpretation. All labels improved nutrition accuracy better than no label. NuVal and MTL led to most accurate estimates of sat fat, sugar, and sodium. Single TL worked best when comparing similar products. None of the labels shifted purchase intentions. |

Lima, et al. |

How do front of pack nutrition labels affect healthfulness perception of foods targeted at children? Insights from Brazilian children and parents |

2018 |

Quantitative. Web based controlled experimental study comparing three different FOP nutrition labeling schemes.

|

|

|

Brazil |

For parents, products with the warning system were rated significantly less healthful than those containing the GDA, whereas the TLS did not significantly differ from the other two systems. Age and socio-economic status influenced the effect of FOP labels on children’s perceived healthfulness. Only 9–12 years old children from middle/high socio-economic status were influenced by FOP labels: the warning system and TLS reduced healthfulness perception of frosted corn flakes compared to the GDA system. |

Lundeberg, et al. |

Comparison of two front-of-package nutrition labeling schemes, and their explanation, on consumers' perception of product healthfulness and food choice |

2018 |

Quantitative. Experimental study n=306 |

|

|

USA |

Star system outperformed traffic light on healthfulness ratings; for both more and less healthful products. Purchase intent was not affected by type of system; participants said they would purchase the healthiest food regardless of system. Information explaining the system, versus the control condition of no explanation, made a difference for products in the mid-range of healthfulness (versus high and low) but there was no difference within the explanation types (gain, loss, loss+ gain). |

Machin, et al. |

Traffic Light System Can Increase Healthfulness Perception: Implications for Policy Making |

2018 |

Quantitative. Experimental study n=1228 |

|

|

Uruguay |

Warning system results similar to simplified traffic light system. For traffic lights, where at least two nutrients were "low in" (green) the product was perceived as healthier even in the presence of a "high in" (red) nutrient. |

Tortora, et al. |

Influence of time orientation on food choice: Case study with cookie labels |

2018 |

Quantitative. 1. A choice conjoint task was designed using labels differing in type of cookie (chocolate chips vs. granola), FOP nutrition information (nutritional warnings vs. Facts Up Front system) and nutritional claim (no claim vs. “0% cholesterol. 0% trans fat”) 2.155 participants evaluated 8 pairs of cookie labels and selected the one they would buy if they were in the supermarket n=155 |

|

|

Uruguay |

|

Author |

Title |

Year |

Method |

FOP |

FOP Image |

Country |

Highlights of Findings |

|

Acton, Vanderlee, & Hammond |

Influence of front-of-package nutrition labels on beverage healthiness perceptions: Results from a randomized experiment |

2018 |

Quantitative.

675 participants |

|

|

Canada |

3. Consumers indicated almost unanimous support for implementing FOP nutrition labeling systems. |

|

Ares, Varela, Machin, et al |

Comparative performance of three interpretative front-of-pack nutrition labelling schemes: Insights for policy making |

2018 |

Quantitative.

|

|

|

Uruguay |

|

|

Billich, Blake, Backholer, et al |

The effect of sugar-sweetened beverage front-of-pack labels on drink selection, health knowledge and awareness: An online randomised controlled trial |

2018 |

Quantitative.

|

|

|

Australia |

drinks. |

|

Egnell, Ducrot, Touvier, et al |

Objective understanding of Nutri-Score Front-Of-Package nutrition label according to individual characteristics of subjects: Comparisons with other format labels |

2018 |

Quantitative. Experimental - Online 3,751 (started w/ 4,328) |

Nutri-Score, MTL, Sens |

|

France |

Compared France's Nutri-Score label with MTL, and a modified reference intake graphic. Compared to no label, all FOP's were significantly associated with an increase in the ability to classify the product, but Nutri-Score outperformed the others on although results varied widely between logos. |

|

Egnell, Kesse- Guyot, et al |

Impact of Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels on Portion Size Selection: An Experimental Study in a French Cohort |

2018 |

Quantitative. Experimental - Online n= 25,772 |

Nutri-Score, MTL, Evolved Nutrition Label |

|

France |

Study focused mainly on testing the effect of the EnL (a modified MTL developed by industry) compared to other FOP's on portion size. Compared to no label, the Nutri-Score resulted in lower portion sizes, followed by the MTL. The ENL (an adaption of the MTL) only lowered portion sizes for cheese but increased it for spreads. |

|

Hamlin and McNeill |

The Impact of the Australasian 'Health Star Rating', Front-of-Pack Nutritional Label, on Consumer Choice: A Longitudinal Study |

2018 |

Quantitative. Field experiment - two supermarket exits 1,000 in one location and 1,600 in the other. |

Australia's HSR |

|

New Zealand |

Tested effects of HSR on consumers stated preference for mock breakfast cereals vs. control (no HSR). Neither hypotheses supported; HSR did not affect consumer choice and more stars did not consistently affect choice. (Critique: DV too broad, no covariates and sample too narrowly drawn). |

|

Talati, Pettigrew, Kelly, Ball, Et al |

Can front-of-pack labels influence portion size judgements for unhealthy foods? |

2018 |

Quantitative. Experimental - Online N=1505 |

Daily Intake Guide; Multiple Traffic Light; Health Star Rating |

|

Australia |

Compared FOP effect on portion size; included a no-FOP control; used unhealthy pizza, cookies, yoghurts, and cornflakes. HSR and MTL resulted in small but significant reduction in portion size for some of the products; Pizza and cornflakes for HSR; Cornflakes for MTL. Concluded that the more interpretive labels (HSR & MTL) worked better than less interpretive (DIG) for reducing portion sizes. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Acton, et al. |

Exploring the main and moderating effects of individual-level characteristics on consumer responses to sugar taxes and front-of-pack nutrition labels in an experimental marketplace |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1.

Warning label (WL) |

|

Canada |

1.

FOP systems differ in the extent to which they promote or

dissuade purchases |

|

Baccelloni et al. |

Effects on Consumers' Subjective Understanding and Liking of Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels: A Study on Slovenian and Dutch Consumers |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1.

NutrInform Battery |

|

Slovenia and the Netherlands |

1.

NutrInform Battery registered a better performance than

Nutri-Score in all 3 sub-dimensions of subjective understanding,

comprehensibility, help-to-shop, and complexity in both

countries. |

|

Bandeira, et al. |

Performance and perception on front-of-package nutritional labeling models in Brazil |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1.

Octagon |

|

Brazil |

1.

All FOPs increased

understanding of the nutritional content, reduced perception of

healthiness and purchase intentions compared to control. |

|

Bossuyt, et al. |

Nutri-Score and Nutrition Facts Panel through the Eyes of the Consumer: Correct Healthfulness Estimations Depend on Transparent Labels, Fixation Duration, and Product Equivocality |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1. Nutri-Score |

|

Belgium |

1.

Nutri-Score positively affects accuracy in healthfulness

estimation; NFP had no effect or a negative effect |

|

Carruba, et al. |

Front-of-pack (FOP) labelling systems to improve the quality of nutrition information to prevent obesity: NutrInform Battery vs Nutri-Score |

2021 |

Qualitative |

1.

NutrInform Battery |

|

Italy |

1.

Nutri-Score limited by providing assessment based on 100 g

instead of a usual portion. |

|

Constantin, et al. |

A human rights-based approach to non-communicable diseases: mandating front-of-package warning labels |

2021 |

Qualitative |

Various |

No image available |

Americas |

1.

FOP warning labels with excessive critical nutrients are the most

effective FOP system |

|

Dubois, et al. |

Effects of front-of-pack labels on the nutritional quality of supermarket food purchases: Evidence from a large-scale randomized controlled trial |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1.

SENS |

|

France |

1.

Only modest effects on nutritional quality of foods purchased in

the four categories: Nutri-Score was most effective FOP,

but only effect was to increase purchases of foods in the top

third of their category by 14%; no effect on purchases of foods

with medium, low, or unlabeled quality. |

|

Esfandiari, et al. |

Effect of Face-to-Face Education on Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Toward "Traffic Light" Food Labeling in Isfahan Society, Iran |

2021 |

Quantitative |

Traffic Light (TL) |

|

Iran |

1.

Education significantly increased scores for knowledge,

attitudes, and practices |

|

Fialon, et al. |

Is FOP Nutrition Label Nutri-Score Well Understood by Consumers When Comparing the Nutritional Quality of Added Fats, and Does It Negatively Impact the Image of Olive Oil? |

2021 |

Quantitative |

Nutri-Score |

|

Spain |

80%

felt Nutri-Score was useful |

|

Folkvord, et al. |

The effect of the Nutri-Score label on consumer’s attitudes, taste perception and purchase intention: An experimental pilot study |

2021 |

Quantitative

and Qualitative |

Nutri-Score |

|

The Netherlands |

Nutri-Score label had no effect on consumers' attitudes, taste perception, and purchase intention. |

|

Goiana-da-Silva, et al. |

Nutri-Score: The Most Efficient Front-of-Pack Nutrition Label to Inform Portuguese Consumers on the Nutritional Quality of Foods and Help Them Identify Healthier Options in Purchasing Situations |

2021 |

Quantitative

|

1.

Health Star Rating (HSR) |

|

Portugal |

1.

All 5 FOPs led to better ranking of healthfulness compared to no

label |

|

Hock, et al. |

Experimental study of front-of-package nutrition labels' efficacy on perceived healthfulness of sugar-sweetened beverages among youth in six countries |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1.

Health Star Rating (HSR) |

|

Australia, Canada, Chile, Mexico, UK and US |

1.

All 5 FOPs effective

in reducing the perceived healthfulness of sugar-sweetened

beverages |

|

International Food Information Council |

IFIC Survey: Knowledge, Understanding and Use of Front-of-Pack Labeling in Food and Beverage Decisions Insights from Shoppers in the U.S. |

2021 |

Quantitative |

Not specified |

No image available |

U.S. |

1.

Half find FOP

impactful, but

nutrition facts panel and list of ingredients were slightly

higher ranked |

|

Kontopoulou, et al. |

Online Consumer Survey Comparing Different Front-of-Pack Labels in Greece |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1.

Multiple Traffic Lights (MTL) |

|

Greece |

Nutri-Score label presented greater improvements when compared to the GDA label |

|

Marette, Stéphan |

Ecological and/or Nutritional Scores for Food Traffic-Lights: Results of an Online Survey Conducted on Pizza in France |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1.

Red label |

No image available |

France |

1.

Scores and labels significantly affect purchase intentions |

|

Mauri et al. |

The effect of front‐of‐package nutrition labels on the choice of low sugar products |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1.

Traffic light |

No image available |

U.K. |

1.

Sugar teaspoons more effective than traffic light in signaling

sugar level and helping consumers make healthier choices. |

|

Mediano Stoltze, et al. |

Impact of warning labels on reducing health halo effects of nutrient content claims on breakfast cereal packages: A mixed-measures experiment |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1.

Warning labels |

|

Chile |

1.

No significant interaction between WL and NC claims |

|

Medina-Molina |

Analysis of the moderating effect of front-of-pack labelling on the relation between brand attitude and purchasing intention |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1. Nutri-Score |

|

Spain |

1. FOP does not modify the relation between brand attitude and purchase intent, though some variation by gender. |

|

Roudsari; Pouri Hosseini; Bonab; Zahedi-rad; Nasrabadi; Zargaraan |

Consumers' perception of nutritional facts table and nutritional traffic light in food products' labelling: A qualitative study |

2021 |

Qualitative |

1. Traffic Light Label |

|

Iran |

1.

Large number of participants not aware of NFT or TLL |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scapin, et al. |

Influence of sugar label formats on consumer understanding and amount of sugar in food choices: a systematic review and meta-analyses |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1.

Traffic light label (TLL) |

No image available |

International |

1.

Label formats using “high in sugar” interpretative

texts (traffic light labels and warning signs) were most

effective in increasing consumers’ understanding of the

sugar content in packaged foods. |

|

Shahrabani, et al. |

The impact of Israel's Front-of-Package labeling reform on consumers' behavior and intentions to change dietary habits |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1. Red/green labels |

No image available |

Israel |

1.

More than half reported using the FOPs to some extent |

|

Sinu Scientific; Sinu Scientific |

Front-of-pack" nutrition labeling" |

2021 |

Qualitative |

1.

Nutri-Score (NS) |

No image available |

International |

1.

NB is more focused toward the primary goal of FOPs, which is to

fight malnutrition by excess as a contributor to obesity and

non-transmissible disease |

|

Song, et al. |

Impact of color-coded and warning nutrition labelling schemes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis |

2021 |

Quantitative |

Various |

No image available |

International |

1.

Traffic light labelling systems, nutrient warning, and health

warning labels associated with selecting more healthful

products |

|

Thomas; Seenivasan; Wang |

A nudge toward healthier food choices: the influence of health star ratings on consumers' choices of packaged foods |

2021 |

Quantitative |

1. Health Star Rating (HSR) |

|

Australia |

1.

HSR increased the choice of the healthier option when nutrients

were negatively correlated |

|

Zafar, et al. |

Readable Labels and Moderating Effect of Individual Personality Traits Effect on Consumer Healthy Packaged Food Selection Intention |

2021 |

Qualitative and Quantitative To examine factors affecting consumer intention to select healthy packaged food. 713 participants completed a questionnaire asking about purchase intentions for products with traffic lights label, health statements, efficacy and intention for selecting healthy food items 32 qualitative interviews assessing attitudes toward labels, effect of personality traits on intentions |

1. Traffic lights 2. Health Statements |

No image available |

Pakistan |

FOPs had insignificant effect on purchase intentions without label reading attitude; results highlight the need for consumer education regarding nutrients. |

|

Acton, et al. |

Comparing the Effects of Four Front-of-Package Nutrition Labels on Consumer Purchases of Five Common Beverages and Snack Foods: Results from a Randomized Trial |

2022 |

Quantitative |

1.

Warning label (WL) |

|

Canada |

1.

Participants seeing HSR more likely to purchase 100% fruit juice

(compared to MTL) and cheese snacks (compared to no label and

WL |

|

Adasme-Berríos, et al. |

Effect of Warning Labels on Consumer Motivation and Intention to Avoid Consuming Processed Foods |

2022 |

Quantitative 2. 807 participants who purchased processed foods with warning labels completed a questionnaire asking about food behaviors, nutritional knowledge, and how they choose foods. |

1. Stop sign |

No image available |

Chile |

1. Nutrition warnings effective to help mitigate eating motivations and to boost intention to avoid processed food |

|

Agarwal, et al. |

The effect of energy and fat content labeling on food consumption pattern: a systematic review and meta-analysis |

2022 |

Qualitative |

Various |

No image available |

International |

1.

Although the 6 studies claimed that labeling did not reduce the

consumption of energy or fat, meta-analysis showed that fat and

energy labeling had a statistically significant effect on

consumption |

|

Ahn and Lee |

Effect of NUTRI-SCORE labeling on sales of food items in stores at sports and noNutri-Scoreports facilities |

2022 |

Quantitative |

1. Nutri-Score |

|

Korea |

1.

In sports facilities, sales were higher for relatively healthy

foods compared to less healthy. |

|

Andreeva, et al. |

Polish Consumers' Understanding of Different Front-of-Package Food Labels: A Randomized Experiment |

2022 |

Quantitative |

1.

Health Star Rating (HSR) |

|

Poland |

1.

Relative to RI's, Nutri-Score showed significant improvement in

objective understanding of FOP. |

|

Bhattacharya |

Consumers' Perception About Front of Package Food Labels (FOP) in India: A Survey of 14 States |

2022 |

Quantitative |

1.

Warning Labels (WL) |

No image available |

India |

1.

Majority of participants consumed packaged foods and were aware

of the food package labeling; most (89%) considered the labels

helpful. |

|

Bhawra, et al. |

Correlates of Self-Reported and Functional Understanding of Nutrition Labels across 5 Countries in the 2018 International Food Policy Study |

2022 |

Quantitative |

1.

Health Star Rating (HSR) |

|

Australia, Canada, Mexico, UK and US |

1.

FOP understanding significantly higher for interpretive label

systems (HSR, Traffic lights) compare with Guideline Daily

Amounts |

|

Cabrera, et al. |

Traffic-light nutrition labeling use and demand among Ecuadorean children |

2022 |

Quantitative |

1. Traffic light |

|

Ecuador |

1.

Survey results: 42% of all participants answered all 4 correctly,

22% got between 2 and 3, and 36% got 0 to 1. |

|

Contreras-Manzano, et al. |

Objective understanding of front of pack warning labels among Mexican children of public elementary schools. A randomized experiment |

2022 |

Quantitative |

1.

Traditional warning labels |

|

Mexico |

1.

Warning labels led to children identifying healthiest or least

healthy items most correctly and in the least amount of time |

|

Cordero-Ahiman, et al. |

Responsible Marketing in the Traffic Light Labeling of Food Products in Ecuador: Perceptions of Cuenca Consumers |

2022 |

Quantitative |

1. Traffic light nutrition labels |

No image available |

Ecuador |

1.

Education, knowledge of labeling, and knowledge of marketing were

associated with understanding of traffic light nutrition

labels. |

|

Correa et al. |

Why Don't You [Government] Help Us Make Healthier Foods More Affordable Instead of Bombarding Us with Labels? Maternal Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practices after Full Implementation of the Chilean Food Labelling Law |

2022 |