Supporting statement 3.14.07

Supporting statement 3.14.07.doc

Head Start Impact Study (HSIS)

OMB: 0970-0229

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation

Administration for Children and Families

Third Grade Follow-Up to the

Head Start Impact Study

Office of Management and Budget

Clearance Package Supporting Statement

And Data Collection Instruments

November 3, 2006

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A. Justification 1

A.1 Explanation Of The

Circumstances Which Make The Data Collection

Necessary 1

A.2 How The Information Will

Be Collected, By Whom It Will Be

Collected, And For What

Purpose 10

A.3 Use Of Automated,

Electronic, Mechanical, Or Other

Technological Collection

Techniques 16

A.4 Efforts To Identify Duplication 18

A.5 Minimizing Impact On Small Businesses Or Other Small Entities 19

A.6 Consequences If The Collection Is Not Conducted 19

A.7 Special Circumstances 19

A.8 Consultation With Persons Outside The Agency 19

A.9 Remuneration To Respondents 20

A.10 Assurances Of Privacy 23

A.11 Questions Of A Sensitive Nature 23

A.12 Respondent Burden 24

A.13 Total Annual Cost Burden 27

A.14 Annualized Cost To The Government 27

A.15 Reasons For Any Program Changes 27

A.16 Plans For Tabulation And Statistical Analysis And Time Schedule 27

A.17 Approval To Not Display The OMB Expiration Date 46

A.18 Exception To The Certification Statement 46

B. Collections Of Information Employing Statistical Methods 49

B.1 Potential Respondent Universe 49

B.2 Description Of Sampling And Information Collection Procedures 49

B.3 Methods To Maximize Response 58

B.4 Tests Of Procedures To Minimize Burden 60

B.5 Identity Of Individuals

Consulted On Statistical Aspects Of

Design And Identity Of

Contractors 61

Bibliography 62

Appendix A Data Collection Instruments

Appendix B Federal Register Announcement

Appendix C Public Comments

Appendix D Advisory Committee Members

Appendix E Head Start Impact Study Sampling Plan

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 Number of Children in the Head Start and Non-Head Start

Groups by Age Cohort 11

Table 2 Percent of HSIS Parent Interviews and Child Assessments

Complete By Data Collection Period 11

Table 3 Data Collection Schedule 12

Table 4 Data Collection Instruments and Activities 22

Table 5a Estimated Response Burden for Respondents in the Third Grade

Follow-Up to the Head Start Impact Study-Spring 2007 25

Table 5b Estimated Response Burden for Respondents in the Third Grade

Follow-Up to the Head Start Impact Study-Spring 2008 26

Table 6 Hypothetical Example: Impact of Head Start on Access to

“Quality” elementary School Teachers 29

Table 7 Project Deliverables and Delivery Dates 47

Table 8 Expected Sample Sizes in the Third Grade Follow-Up Study 50

Table 9a Minimum Detectable Effect Sizes with Power = .8

for the Third Grade Follow-Up Sample 54

Table 9b Minimum Detectable Differences in Proportions with

Power = .8 for the Third Grade Follow-Up Sample, Based

on Spring 2003 HSIS Data 54

LIST OF FIGURES

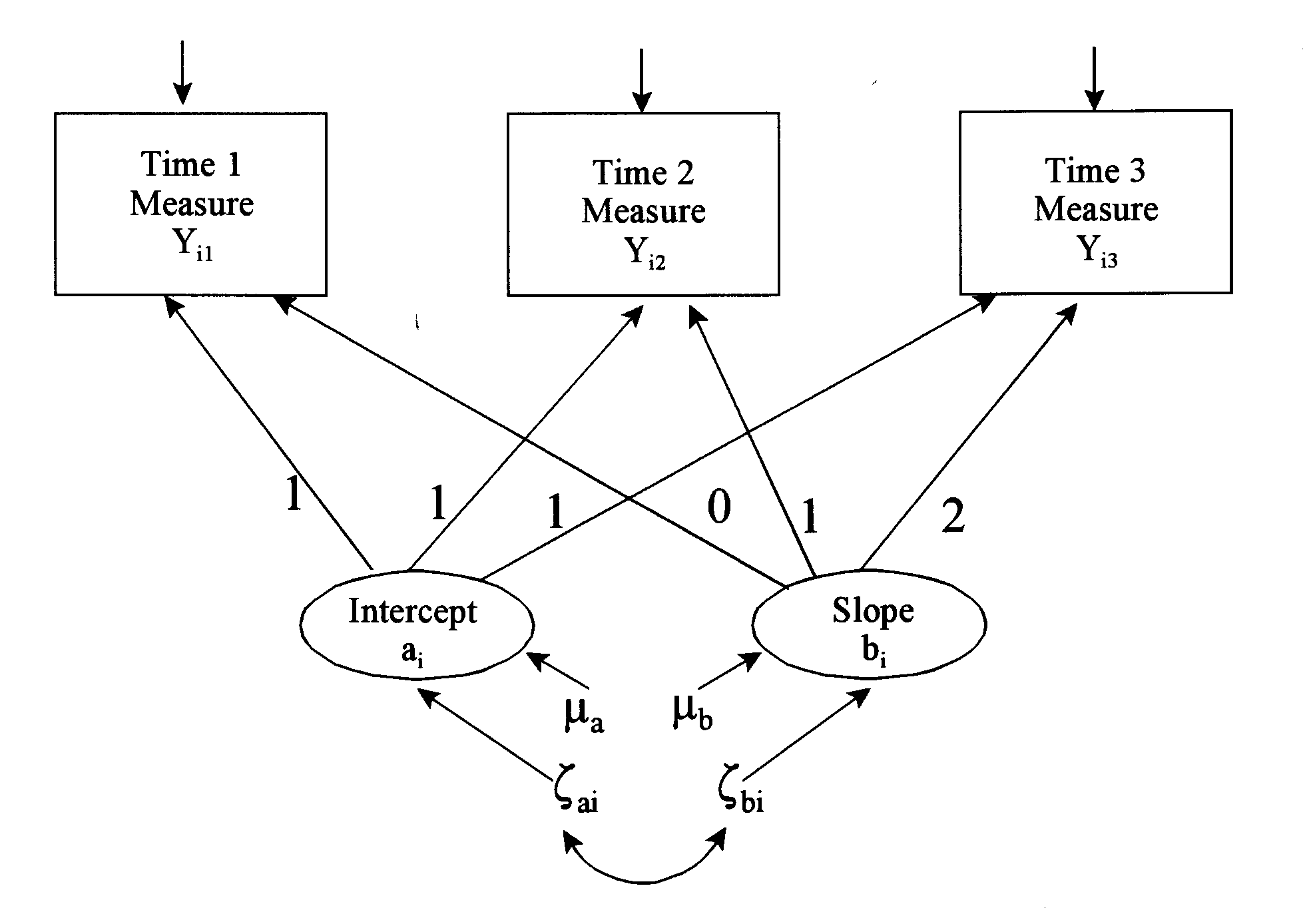

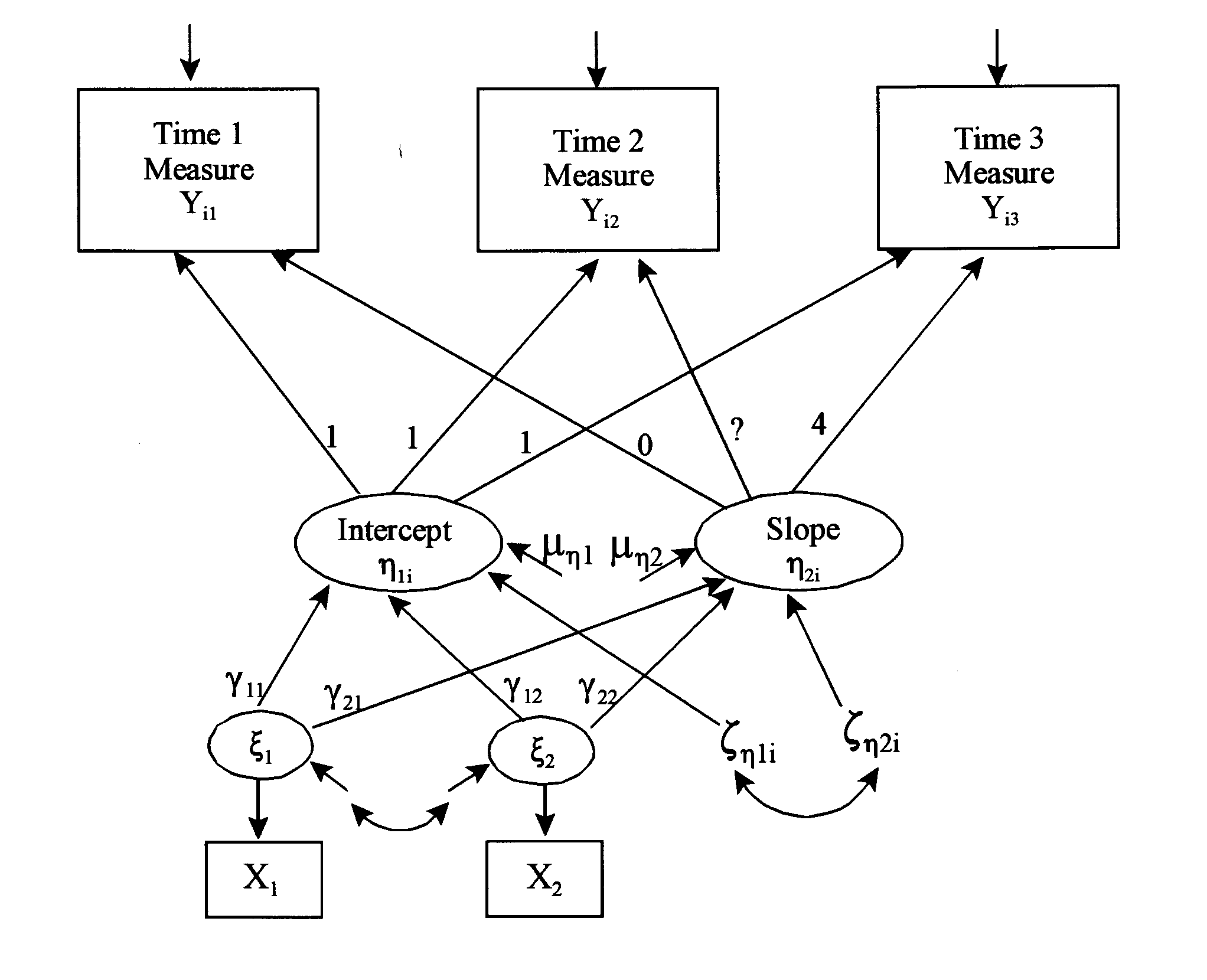

Figure 1 Unconditional and Conditional Latent Growth Models 43

List of Instruments

Child Assessment (Spanish and Bilingual versions available)

Parent Interview (Spanish version available)

Teacher Survey and Teacher/Child Report Form (Spanish version available)

Principal Survey (Spanish version available)

A. JUSTIFICATION

A.1 Explanation of the Circumstances Which Make the Data Collection Necessary

The Office of the Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), is submitting this Request for OMB Review in support of the Third Grade Follow-Up to the Head Start Impact Study (Third Grade Follow-Up Study). OMB approved the initial package for the Head Start Impact Study (HSIS) in September 2002 (OMB # 0970-0229, Expiration Date: 09/30/2005 and the HSIS continuation OMB # 0970-0029, Expiration Date: 07/30/2006). The purpose of the Third Grade Follow-Up Study is to build upon the existing randomized control design in the HSIS in order to determine the longer term impact of the Head Start program on the well-being of children and families. Specifically, the study will examine the degree to which the impacts of Head Start on initial school readiness are altered, maintained or perhaps expanded by children’s school experiences and the various school quality and family/community factors that come into play up to and during the third grade. The Third Grade Follow-Up Study also is designed to build on the comprehensive instrument design and data collection plans effectively implemented in the HSIS.

Background

Overview of Head Start. Over the years, Head Start has served nearly 23 million preschool children and their families since it began in 1965 as a six-week summer program for children of low-income families. The program provides comprehensive early child development services to low-income children, their families, and communities. Head Start has evolved over time to include a wide variety of program options based on the specific situations and resources of the communities to meet the changing needs of the children and families it serves. Variations in services include, but are not limited to, programs offering center-based services, home-based services, part-day enrollment, full-day enrollment and/or one or two years of services. In addition, many programs are now partnering with non-Head Start agencies and/or combining funds from various sources to coordinate services that best address the needs of children and families.

As Head Start’s Federal appropriation has grown, ($96 million in summer 1965 to $6.8 billion in 2005) so have initiatives calling for improved outcomes and accountability (e.g., Chief Financial Officers Act, Government Performance and Results Act of 1993). During the rapid expansion of Head Start, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) released two reports underlining the lack of rigorous research on Head Start’s effectiveness noting that “…the body of research on current Head Start is insufficient to draw conclusions about the impact of the national program" (GAO, 1997). The 1998 report added, “…the Federal government’s significant financial investment in the Head Start program, including plans to increase the number of children served and enhance the quality of the program, warrants definitive research studies, even though they may be costly” (GAO, 1998).

Based upon GAO recommendation, and the testimony of research methodologists and early childhood experts, Congress mandated in Head Start’s 1998 reauthorization that DHHS conduct research to determine, on a national level, the impact of Head Start on the children it serves. Congress called for an expert panel to develop recommendations regarding the study design to “…determine if, overall, the Head Start programs have impacts consistent with their primary goal of increasing the social competence of children, by increasing the every day effectiveness of the children in dealing with their present environments and future responsibilities, and increasing their school readiness” (42 USC 9801, et.seq.). The research should also consider variables such as whether Head Start strengthens families as the nurturers of their children and increases children’s access to other education, health, nutritional, and community services.

To design such a study, the Department convened a committee of distinguished experts, the Advisory Committee on Head Start Research and Evaluation, that considered the major issues and challenges in designing a rigorous research study that is both credible and feasible, and the committee recommended a framework for the design of the Head Start Impact Study (HSIS). A contract was awarded in October 2000 to Westat, in collaboration with the Urban Institute, American Institutes for Research, and Decision Information Resources to conduct the Head Start Impact Study as mandated by the Coats Human Services Amendments of 1998, PL 105-285.

The National Head Start Impact Study is a longitudinal study that involved approximately 5,000 three- and four- year old preschool children across an estimated 75 nationally representative grantee/delegate agencies (in communities where there are more eligible children and families than can be served by the program). Children were randomly assigned to either a Head Start group that had access to Head Start program services or to a non-Head Start group that could enroll in available community non-Head Start services, selected by their parents. Data collection began in fall 2002 and continued through spring 2006, following children through the spring of their first-grade year. The HSIS data collection included parent interviews, teacher and care provider surveys, child assessments, direct observations of the quality in different care settings, and teacher/care provider ratings of children. Although the Third Grade Follow-Up Study will be based largely on work that has already been completed for the HSIS, it offers an opportunity to examine the degree to which the impacts of Head Start on initial school readiness are changed by children’s third grade school experiences and the family/community factors associated with the child during the school years. This study allows us to broaden the scope of analysis to include factors that have not yet been examined as part of the HSIS.

The implementation of the Third Grade Follow-Up Study must be understood within the history of the preschool and Head Start research and evaluation efforts. Crucial to the study is understanding the evidence as it concerns preschool experiences influence on outcomes in elementary school.

Preschool Intervention Studies. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of experimental design studies examining preschool intervention and even fewer preschool intervention studies with longitudinal designs that stretch beyond kindergarten or first grade. Use of experimental design is concentrated on a few studies such as the Abecedarian Project, Project CARE, and the Early Training Project. These studies randomize families matched on control variables (e.g., income, gender) and place some into preschool intervention while excluding others. This allows researchers to determine the effects of treatment by comparing treated children and families to those that were similar at the start of the study and whose experiences differ only in terms of whether or not they received the intervention. When the experiments involve high intensity programs (i.e. extensive instruction, comprehensive services, home visits), generalization is difficult. High intensity projects are often considered too costly and resource intensive to be replicated on a national scale. It is often their small sample size that makes them feasible for researchers to conduct them. For example, the initial Abecedarian sample consisted of 117 participants (Campbell & Ramey, 1995). Moreover, findings from intense programs cannot always be expected to be replicated by more moderate programs. This is due to evidence that the intensity of a preschool intervention can increase the positive effect those programs exert on child outcomes (Nelson et al., 2003; Ramey & Ramey, 2004).

More common are studies that explore early experience predictors to school-age outcomes (e.g., Miles & Stipek, 2006; Peisner-Feinberg et al., 2001) and quasi-experimental designs intended to determine the causal contribution of specific experiences or programs to those outcomes. Quasi-experimental include wait-list designs that compare children who receive an intervention such as Head Start to those who are waiting for the opportunity to enroll, and regression-discontinuity approaches that rank children on level of need and adjust for these and other differences in comparing outcomes of participants and nonparticipants. The Chicago Longitudinal Study and the work of Abbott-Shim and colleagues at the Georgia State University Quality Research Center (2003) are two examples of such work. Although ethical concerns often call for them, quasi-experimental designs generally can not provide the clarity of data obtained through true experimental studies. Other studies that explore relationships between variables provide useful information to guide research hypotheses regarding the aspects of preschool interventions that are most likely to predict later child outcomes. For example, Peisner-Feinberg and colleagues (2001) reported a positive relationship between the quality of preschool care and elementary math scores. However, the question of long-term impacts of preschool interventions is best answered through longitudinal data from studies allowing the direct comparison of children who received the intervention to those who did not—and, ideally, comparing sets of children who are indistinguishable at the outset by virtue of having been selected at random from a common pool of eligible applicants.

Summarized below are some of the findings about the effects of preschool participation on children’s later outcomes.

Cognitive Outcomes. It is clear that preschool participation can have lasting cognitive and academic effects (Barnett, 1995; Miller & Bizzell, 1984; Nelson, Westhues, & MacLeod, 2003). For example, children who attend preschool are less likely to be held back at grade level or to be in special education classes (Darlington, Royce, Snipper, Murray, & Lazar, 1980). Further, the NICHD Early Child Care Research Study linked high-quality child care with higher school-age math and reading test scores (NICHD ECCRN, 2005).

Social Outcomes. Social outcomes such as socialization skills (e.g., Barnett, 1995; Hubbs-Tait et al., 2002) and juvenile delinquency (e.g., Garces, Thomas, & Curie, 2002; Reynolds, Ou, & Topitzes, 2004) are also positively influenced by preschool attendance. For example, children observed to have close relationships with their preschool teacher have been found to have higher attention and sociability ratings in the second grade as well as displaying fewer problem behaviors (Peisner-Feinberg et al., 2001). Further, in their meta-analysis of over 60 studies, Paro and Pianta (2000) concluded that measures of social outcomes taken soon after preschool explained a significant portion of the variance for assessments of social outcomes taken later in elementary school, albeit with small effect sizes.

Experimental Evidence. Experimental data on preschool provides further evidence of the long-term effects of preschool intervention. For example, the Abecedarian study reported that children in a preschool intervention group performed better on cognitive tests in third grade than those who had not had the intervention (Campbell & Ramey, 1995). Similar results were found for fourth graders who had summer interventions during the preschool period (Gray & Klaus, 1970); children who had received intervention outperformed control children on intelligence tests. It should be noted that the entire sample in the Campbell and Ramey (1995) study saw a decline in cognitive scores following the first grade, however, children who had intensive preschool interventions experienced less change over time.

Head Start Evidence Studies examining the effects of a national program such as Head Start have the potential to be more generalizable. However, taken as a whole, the literature yields inconsistent results as to the program’s success after kindergarten. For example, a study following Head Start children who took part in a Post-Head Start Transition program through the third grade found no achievement gains for the participants (Bickel & Spatig, 1999). However, it is reasonable to question whether the transition program elements were sufficient to maintain Head Start gains. Further, there is no control group with which to compare the progress of the children in the transition program to the progress of children not in the program or to those who had never attended Head Start. Finally, the limited sample in the Post-Head Start Transition program makes generalizations of any findings to a national sample of Head Start difficult.

Other data suggest that Head Start programs can have lasting effects. For example, one study found that female Head Start participants narrowed the gender gap in math (Kreisman, 2003). Findings also suggest that Head Start participation improves school readiness which can lead to enhanced school performance throughout elementary school (Abbott-Shim, Lambert, & McCarty, 2003, Lee, Brooks-Gunn, Schnur & Liaw, 1990). Data relating child care quality to positive child outcomes in third grade also point to potential benefits of Head Start participation (Burchinal, Roberts, Zeisel, Hennon, and Hooper, 2006; NICHD ECCRN, 2005). Considering that a national study of Head Start centers found that, on average, Head Start quality is on par with or better than alternate center-based child care options (Zill et al., 2003) it is reasonable to anticipate positive outcomes as a result of enrollment in the program.

Ongoing Longitudinal Efforts. Currently there are a number of longitudinal study efforts collecting valuable data regarding preschool and school-age experiences. Although not all of these studies focus exclusively on Head Start populations, all are collecting data that will allow examinations of the relationship between Head Start experiences and school-age outcomes. The studies are the Head Start Family and Child Experiences Survey (FACES), the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation Project (EHS), the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey – Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K), and the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey – Birth Cohort (ECLS-B). While these studies have provided and will continue to provide valuable data regarding the variety and nature of experiences of young children and their families as well as the relationships between those early experiences and later outcomes, the HSIS and the Third Grade Follow-Up Study will expand upon the knowledge gained from these combined research efforts.

The HSIS and the Third Grade Follow-Up Study provide the opportunity to explore questions related to Head Start using a nationally representative sample. The relevance of findings reported by these studies will not be biased by programmatic anomalies or limited by regional sample characteristics but will be applicable to the whole of the Head Start population. Further, the experimental design of the study allows for the comparison of children and families whose only significant difference is the treatment in question (i.e. access to Head Start). The preliminary results from the first year report show that Head Start increases 3-year-old children’s cognitive and social emotional development and children’s health as well as positive parenting practices (all the domains examined in the study). Impacts were found on some measures in each of these four domains. Findings were also positive, though less prevalent, for 4-year-olds. The lasting effect of these impacts has not yet been examined at the kindergarten or first grade level. The Third Grade Follow-Up Study will provide the opportunity to assess whether these effects were maintained or diminished or whether new effects occur.

Third Grade Environment. The onset of third grade highlights big changes in children’s understanding of their world as well as changes in the classroom instruction that they will receive. The children assessed as third graders will see the world in a markedly different way than they did just two years prior. Cognitively, most students at this age move from Piaget’s preoperational to concrete operational stage. Hallmarks of the concrete operational stage include more logical thought processes and the ability to take others’ perspectives into account (Piaget, 1983).

Evidence from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development leads us to expect a great deal of variability between the third grade classrooms of sample children. However, on average instruction will focus on basic skills with special emphasis given to literacy skills. Furthermore, though structural classroom factors were somewhat stable from first to third grade in the NICHD study, aspects such as teacher sensitivity and number of literacy and math activities were not strongly related across that span (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2005).

No Child Left Behind. Further, the Third Grade Follow-Up Study will be conducted in the context of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) implementation. The passage of the NCLB Act in 2001 attached consequences to its push for standards and accountability in public schools. Especially vulnerable to the potential consequences of NCLB are schools receiving Title 1 funding. As of 2002, 58% of all public schools, including 67% of elementary schools, received Title I funds (U.S. Department of Education, 2002). It is likely that many children from the Head Start sample will find themselves in such schools as Title I funds are targeted at low-income children.

Against the backdrop of NCLB requirements, many schools are experiencing powerful pressure to improve test scores. By the time the third graders in the Third Grade Follow-Up Study are assessed, schools will be required to test students annually in reading and language arts, and mathematics. Schools that have been designated as “in need of improvement” are likely to be experiencing particular pressure from administrators and parents to produce good test scores. Thus the Third Grade Follow-Up Study will have to take into consideration the possible effects on the findings of this test focus. For example, some schools may implement extra services or supports for third graders to help improve their test scores while others may not. In addition, data collection might be complicated by schools and teachers resistant to study demands on students’ time, even if few students are being assessed as part of the study. Assessing the impact of access to Head Start on children’s school performance will require consideration of their varied school experiences and the initiatives that individual schools are implementing. At the same time, analytic approaches incorporating school experiences may require foregoing true “experimental” analyses (i.e., those that compare program group children to control group children with no subgroups based on experience occurring post-random assignment).

Purpose of the Study

The primary purpose of the Third Grade Follow-Up Study is to answer questions about the longer term impact of Head Start through children’s third grade year, including for whom and under what circumstances these impacts differ. This study will provide the opportunity to assess whether early differences between the treatment and control children were sustained through the first 4 years of school. The first-year results of the HSIS show effects on skills such as letter identification and spelling but not on oral comprehension, with effect sizes ranging from approximately 0.1 to 0.3. Some contend that for there to be a lasting effect of preschool outcomes, larger effects and higher order skills need to be achieved. Controversy about fade out of impacts goes as far back as Head Start’s beginnings (M. Wolff and A. Stein, 1996). By measuring treatment and control cognitive differences, this study will help inform the fade out question.

In assessing third grade impacts, it is necessary to consider what new constructs and new skills should be assessed in the children and families in the study. There is concern that the biggest learning problem after the third grade is that disadvantaged students do not understand how to deal with ideas, generalizations, or abstractions as a result of a lack of experience in talking with adults about ideas (Pogrow and Stanley, 2000). Pogrow described this as students hitting a cognitive wall as they proceed in school and the curriculum continues to become more complex. Understanding whether the cognitive gains associated with access to Head Start were sufficient to impact children’s comprehension skills is a key issue for this study.

It will also be important to identify and measure the dominant factors affecting third grade performance. These factors include child characteristics, parent characteristics and practices, home environment, as well as an accumulation of pre-school and school experiences. A particular challenge of all evaluations is to sort out the role each of these variables plays in mediating children’s outcomes. While the experimental design of this study helps to clarify causal paths from the intervention to the outcomes, and with respect to factors established prior to random assignment such as child and family demographic characteristics, many of the variables of interest concern factors that emerged after random assignment (e.g., school experiences and child-parent interactions). This complicates the ability to isolate cause and effect relationships across the range of important influences on child development, Head Start among them. However, data acquired during this study may illuminate which factors contribute to the sustained impact of access to Head Start and which factors detract from it. It is likely to be the interaction of multiple variables that are most predictive of outcomes rather than simple linear relationships.

Research Questions

The Advisory Committee on Head Start Research and Evaluation (1999) recommended that the Head Start Impact Study address the following research questions: What difference does Head Start make to key outcomes of development and learning (and in particular, the multiple domains of school readiness) for low-income children? What difference does Head Start make to parental practices that contribute to children’s school readiness? Under what circumstances does Head Start achieve the greatest impact? What works for which children? What Head Start services are most related to impact?

In the development of the HSIS, the research questions were restated into a set of overall program impact questions, and a set of questions that focus on the relationship between program impacts and children’s experiences after random assignment (Westat, 2005). The preliminary research questions for the Third Grade Follow-Up Study follow this format, with some adaptations to reflect the focus on third grade outcomes.

Direct Impact of Access to Head Start on Children’s Outcomes. These questions address whether children’s third grade outcomes differ depending on whether a child had access to Head Start. What is the impact of prior access to Head Start on children’s cognitive development at the end of third grade? What is the impact of access to Head Start on children’s social-emotional development at the end of third grade? What is the impact of access to Head Start on children’s health status at the end of third grade? Does this vary by subgroups?

Potential Indirect Impact of Head Start on Children Through Direct Impact on Parents. What is the impact of prior access to Head Start on parents’ practices and support of their children’s education by the end of third grade? For example, do the parents of third grade children who had access to Head Start report different parenting practices than the parents of third grade children who did not have access to Head Start? Do parental practices in support of their children’s education (e.g., reading to child, taking an active role in their education) vary by subgroups?

Impacts on Experiences and Services. What is the impact of prior access to Head Start on children’s educational experiences and comprehensive services during the early school years? For example, are the characteristics of the schools that are attended by third grade children who had access to Head Start different from schools attended by children who did not have access to Head Start? Does this vary by subgroups?

Linking Experiences to Impacts and Outcomes. How do the estimated impacts of access to Head Start vary by the nature and type of children’s Head Start experiences? If access to Head Start has an impact on the nature and type of children’s experiences, does this impact lead to an impact on child outcomes? In addition, how are third grade outcomes influenced by parenting practices or school characteristics? What are the pathways through which Head Start access influences third grade outcomes? For example, to what extent does the impact of Head Start (e.g., months of attendance) depend upon children’s early experience or to third grade experiences? These questions explore causal linkages between children’s experiences after random assignment and children’s later outcomes, to determine whether any impact on third grade outcomes is because of Head Start’s impact on children’s early school experiences (in the areas of parenting and school characteristics).

The Third Grade Follow-Up Study is an extension of the work conducted for the Head Start Impact Study that was based on the Congressional mandate that DHHS conduct research to determine, on a national basis, the impact of Head Start on the children it serves. This study will build on the HSIS randomized design to examine the longer term impact of Head Start at the third grade level.

A.2 How the Information Will Be Collected, By Whom It Will Be Collected, and For What Purpose

The original HSIS design called for collecting comparable data on two cohorts of newly entering children (a three-year old cohort and a four-year old cohort) and their families who were randomly assigned to either a treatment group (enrolled in Head Start) or a control group (that were not enrolled in Head Start, but were permitted to enroll in other available services in their community selected by their parents or be cared for at home). To draw the national sample, all eligible grantees/Delegate agencies were clustered geographically with a minimum number of eight grantees/delegate agencies within each cluster. The clusters were grouped into 25 strata based on state pre-K and childcare policy1, race/ethnicity of the Head Start children served, urban/rural status, and region. Next, one cluster with probability proportional to the total enrollment of three- and four-year olds in the cluster, was selected from each stratum and approximately three grantee/delegate agencies were randomly selected from each cluster. From each of the 75 randomly selected grantees/delegate agencies, approximately 48 children per grantee/delegate agency were assigned to the Head Start treatment group and about 32 children were assigned to the control group. Sample children could not have been previously enrolled in Head Start. To avoid a sample size shortfall, small centers on the frame were grouped together within a program to perform center groups, each center group with a combined reported first year enrollment of at least 27 children. The selection and random assignment of approximately 5000 children occurred during the Spring/Summer of 2002. The distribution of children by cohort or age group and by status (treatment or control group) are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Number of Children in the Head Start and Non-Head Start Groups by Age Cohort

Age Cohort |

Head Start (Treatment Group) |

Non-Head Start (Control Group) |

Total Sample |

Three-year olds |

1,530 |

1,029 |

2,559 |

Four-year olds |

1,253 |

855 |

2,108 |

Total |

2,783 |

1,884 |

4,667 |

The Third Grade Follow-Up Study will follow the HSIS sample into the third grade. Data collection for this study will occur in the year in which most children in a cohort are in third grade (i.e., for the 4-year-old cohort, in fall 2006 to spring 2007, and for the 3-year-old cohort, in fall 2007 to spring 2008). Many challenges are presented by a longitudinal study with a national sample. Over time, families move and become more difficult to locate. Others, while they can be tracked successfully, move to distant locations that make in-person interviews and assessments difficult and costly. Respondent fatigue may occur where families begin to tire of the study after having been active participants for several rounds of data collection. Interviewers may feel that the study offers them few new challenges as they complete the same data collection tasks each year. New strategies are needed to keep the study fresh and exciting for respondents and interviewing staff. We have been successful in gaining high cooperation from respondents for five rounds of HSIS data collection and four rounds of tracking. High response rates were achieved for the parent interviews and the child assessments as presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Percent of HSIS Parent Interviews and Child Assessments Complete by Data Collection Period

Percent Complete |

|||||||||

|

|

|

Tracking |

|

Tracking |

|

Tracking |

|

Tracking |

|

Fall 02 |

Spring 03 |

Fall 03 |

Spring 04 |

Fall 04 |

Spring 05 |

Fall 05 |

Spring 06 |

Spring 06 4-year-old cohort |

Parent |

86% |

83% |

84% |

81% |

83% |

81% |

83% |

80% |

82% |

Child |

80% |

84% |

|

81% |

|

78% |

|

77% |

|

N=4,667

Built into each wave of data collection for the Third Grade Follow-Up Study is an assumed attrition rate of 2-3 percent. This attrition rate is based on the HSIS experience and includes refusals, children/families who move from the area, and children and families who could not be located.

The data collection plan for the Third Grade Follow-Up Study will build upon the successful procedures implemented in the original HSIS. Data collection will include waves in spring of the third grade years for both cohorts as well as tracking update information in spring 2007 and fall 2007 for the 3-year old cohort and in fall 2007 and spring 2008 for the 4-year old cohort. Child assessments and parent interviews will be conducted in the child’s home in the spring of the child’s third grade year in school. During the spring data collection, information will be collected from each study child’s school principal and teacher(s). School data, such as average class size, school improvement status, and state test scores will also be collected from secondary sources (e.g., CCD (Common Core of Data), etc.). Table 3 provides a summary of the data collection activities.

Table 3. Data Collection Schedule

School Year Cohort 1 (C-1) Cohort 2 (C-2) |

2006-2007 Cohort 1 (second grade) Cohort 2 (third grade) |

2007-2008 Cohort 1 (third grade) Cohort 2 (fourth grade) |

|

Data Source |

Cohort |

Fall Spring |

Fall Spring |

Children |

C-1 |

|

X |

C-2 |

X |

|

|

Parent/Primary Caregiver |

C-1 |

X* |

X* X |

C-2 |

X |

X* X* |

|

Teacher |

C-1 |

|

X |

C-2 |

X |

|

|

Principal |

C-1 |

|

X |

C-2 |

X |

|

|

*denotes the parent update.

The Third Grade Follow-Up Study primarily is using instruments previously approved by OMB and used in the Head Start Impact Study (OMB #0970-0029), Family and Child Experiences Study (OMB #0970-0151), or the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten. The proposed instruments are copyrighted, so only instrument descriptions are provided in Appendix A.

The third-grade child assessment instrument must build on the structure established for the HSIS data collection, accurately measure children’s cognitive development throughout the span of the study, and be adaptive to the different developmental levels of third-grade children. Substantial changes in the instruments will limit the opportunity to do longitudinal analysis of impacts on growth. However, the existing HSIS instruments need to be adapted to focus on the skills and activities appropriate for third grade students. The instruments will continue to measure outcomes that are important from an educational point of view and are likely to be affected by Head Start exposure. Any new tests will have previously demonstrated reliability and validity for Head Start or other low-income populations.

The child assessment will focus on the areas of reading (language and literacy), mathematics, and executive functioning. In addition, children will be asked to respond to a self-report instrument that includes items about school, their attitudes, motivation, relationships and behavior. The total battery will take about 1 hour to administer. We will assess each child using the following instruments: Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K) reading assessment, the Letter-Word Identification, Applied Problems, and Calculation subtests from the Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement, the Numbers Reversed and Auditory Working Memory from the Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities, and the ECLS-K Self-Description Questionnaire (SDQ). In order to continue to measure Spanish language skills, children who were classified as bilingual in the HSIS will also be administered the Batería Woodcock-Muñoz Identificación de letras y palabras. Spanish speaking children (Puerto Rico) will be administered the Identificación de letras y palabras, Comprehensión de textos, Problemas aplicados, and Câlculo tests from the Bateria Woodcock-Munoz Tests of Achievement, the Inversión de números test from the Batería Woodcock-Muñoz Tests of Cognitive Abilities, and translated versions of the Auditory Working Memory test from the Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities and ECLS-K Self-Description Questionnaire.

The ECLS-K third-grade reading assessment built on the 1992 and 1994 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) Fourth-Grade Reading Frameworks and more difficult skills from the ECLS-K kindergarten and first-grade reading assessments. The ECLS-K third-grade assessment measures phonemic awareness, single word decoding, vocabulary, and passage comprehension.

The Letter-Word Identification test from the Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement measures letter and word identification skills. The easier items require the respondent to identify letters. As the items increase in difficulty, the respondent is asked to pronounce words correctly but the respondent is not required to know the meaning. Passage Comprehension requires the respondent to read a short passage and identify a missing key word that makes sense in the context of the passage. Applied Problems requires the respondent to analyze and solve math problems. The respondent is required to listen to the problem, recognize the procedure to be followed, and then perform simple calculations. Calculation measures the respondent’s ability to perform mathematical computations. The Numbers Reversed test measures short tem memory as well as working memory or attentional capacity. The Auditory Working Memory test measures auditory memory span as well as working memory or divided attention. These tests are included in the Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Cognitive Abilities.

The Self-Description Questionnaire (SDQ) used with the third-grade ECLS-K cohort provides a self-report measure of the child’s cognitive and socio-emotional attitudes. In this instrument, the child is asked to respond to a series of items such as “I enjoy doing work in all school subjects” or “I often argue with other kids” using a four-point response format (i.e., “not at all true, a little bit true, mostly true, and very true”). The 42-item SDQ includes both indirect cognitive measures (self-ratings of competence in reading [eight items], mathematics [eight items], and all school subjects [six items]) and socio-emotional questions related to peer relationships (six items) and problem behaviors (i.e., anger and distractibility (seven items) and sad, lonely, or anxious (seven items).

The Batería Woodcock-Muñoz tests administered to the Spanish and bilingual children are similar to the Woodcock-Johnson III tests administered to the English-speaking children.

The child assessment will be administered in the child’s home by a Westat trained field assessor. The assessor will enter the child’s responses into a laptop computer using the Computer-Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI) technology. The SDQ will be designed as an Audio Computer-Assisted Self Interview (ACASI). These technologies are discussed in the next section. The SDQ will be available in Spanish using the ACASI technology.

The parent interview builds upon the HSIS parent interview that includes both parent report of child outcomes and parent outcomes and will take about one hour to administer. The parent interview for the Third Grade Follow-Up Study will include the following cognitive and socio-emotional child outcomes: Parent-Reported Emergent Literacy Scale (PELS); Social Skills and Positive Approaches to Learning (SSPAL); Social Competencies Checklist (SCCL); Total Problem Behavior (TBP); and Parent-Child Relationship. The parent interview also includes health and parenting outcomes such as the following: whether the child has health insurance, whether the child has received dental care, child’s health status, whether the child needs ongoing medical care, whether child received medical care for an injury in the last month, educational activities with child, amount of reading to the child at home, cultural enrichment activities with child, use of physical discipline, school communication, parenting styles, summer learning activities, and parent involvement. Demographic information as well as information on income, housing, and neighborhood characteristics are also collected during the parent interview.

The parent interview will be conducted in the parent’s/primary caregiver’s home by a Westat trained field interviewer who will enter the parent’s’/primary caregiver’s responses into a laptop computer using CAPI technology. The parent interview will be available in both English and Spanish. For parents/primary caregivers who speak neither English nor Spanish, an interpreter will be used.

Ongoing tracking in longitudinal studies is critical to maintaining high response rates. The tracking update form will be used to verify and update if necessary school and contact information. Tracking updates will occur in spring 2007 for the 3-year old cohort, in spring 2008 for the 4-year old cohort, and in fall 2007 for both cohorts. The tracking updates will primarily be conducted over the telephone with in-person follow-up as necessary. Tracking updates will take about 10 minutes to complete.

We will gather specific information about the child’s experiences and development from the perspective of the teacher. The self-administered teacher survey will include questions to obtain biographical information including education and years of experience, inquiries regarding program elements, quality of management, belief scales to assess staff attitudes on working with and teaching children, and the operation and quality of the program. Items on literacy promoting activities, parallel to questions used in the ECLS-K, are included in the teacher instrument. Use of these items provides a national sample benchmark for the measures. The teachers will also be asked to rate each study child in their classroom using the self-administered teacher/child report form. Information will be collected in the following areas: teacher-child relationship, classroom activities, general background, academic skills, school accomplishments, and health and developmental conditions or concerns. A teacher/child rating form will be completed for each study child’s math and reading/language arts class. For additional study children in a class, the teacher will need to complete a separate teacher/child report form for each child. The self-administered teacher survey and teacher/child report form for one child will require about 30 minutes to complete.

The school principal is another source of data for school demographic characteristics and quality indicators for the school, teachers, and classrooms. The self-administered principal survey will take about 20 minutes to complete and will provide information on the overall operation and quality of the program, including teacher performance, staffing and recruitment, overall staff qualifications, teacher education initiatives and staff training, parent involvement, curriculum and assessment, and demographic information.

We will rely on information from secondary sources, such as the Common Core of Data (CCD) or the school or district website, to track a school’s record with respect to such issues as attendance, disciplinary issues, immunizations of children, average test scores, number of children receiving free or reduced school lunch, school improvement status, and teacher/student ratio.

The information collected for the HSIS will be used to measure the impact of Head Start through first grade on the children it served. The Third Grade Follow-Up Study will provide a measure of the impact of Head Start on children through the third grade.

A.3 Use of Automated, Electronic, Mechanical, or Other Technological Collection Techniques

Westat plans to use a CAPI (Computer-Assisted Personal Interview) instrument for the child assessment with a separate ACASI (Audio Computer-Assisted Self Interview) component for the Self-Description Questionnaire. While we used a paper instrument for the original HSIS, we believe that switching to a computer-based approach for the Third Grade Follow-Up Study has certain benefits. The child assessment for the study will include Woodcock-Johnson III subtests that require the establishment of basals and ceilings. A child starts the test at a particular point depending on the child’s grade. The basal criterion is met when the child answers the six lowest-numbered items correctly. If the basal in not obtained in that section, the interviewer/assessor must test backward until the child meets the basal criterion. Once the child meets the basal criterion, the interviewer/assessor then skips to the point at which the test was interrupted. The interviewer/assessor continues to administer the test until the child gives six consecutive incorrect answers, thereby establishing the ceiling. This approach limits the number of questions that need to be asked but can be tricky for the interviewer/assessor to administer correctly. We believe errors in skipping to the wrong section will be avoided by computer-based scoring which directs the interviewer/assessor to the correct section.

The Self-Description Questionnaire is designed to be self-administered to children. We will program this instrument as an ACASI so that the children have the questions read to them by the computer rather than having to read the questions by themselves. We will first use a short tutorial to teach the child how to use the computer while the interviewer/assessor observes to make sure that child can master the task. Following this tutorial, the interviewer/assessor gives the child headphones and moves across from the child to allow the child privacy to complete the self-administered questionnaire.

We believe that using an ACASI with third grade children has several advantages over a paper and pencil interview that is either self-administered or interview-administered. First, using the ACASI addresses concerns about the varied literacy of the children. Because the computer reads the questions and answers (reading each answer as it is highlighted on the screen), children who are poor readers or nonreaders can still complete the instrument.

A second reason to prefer the ACASI is that it gives the child greater privacy to answer the questions and may lead to more honest answers. Some of the questions on the Self-Description Questionnaire are sensitive in nature and previous research has demonstrated the utility of CASI in soliciting more honest answers to sensitive behaviors (Currivan, Nyman, Turner, and Biener, 2004; Des Jarlais et al., 1999; Metzger et al., 2000; Turner, Ku, Rogers, Lindberg, Pleck, and Sonenstein, 1998).

A third reason to introduce the ACASI at this point is because we believe administration using the computer is more likely to capture the children’s interest than a paper assessment. As third grade students, most children will be experienced with computers from school and/or home. We anticipate that they will be able to use the computer with few problems, as has been our experience on other studies with similar populations. Using a computer is an age-appropriate method. We have also found that the ACASI is a faster method of administration than an interviewer-administered method. As the study children have been completing the child assessments now for several years, a fresh approach is required to keep the assessments from becoming stale. An additional advantage to using ACASI is that all children hear the exact same voice reading the questions and answers, which provides for greater standardization.

Because we will use a computer to administer the child assessments, we also will program the parent interview as a CAPI so that the interviewer has just one mode to use for both instruments. Programming the parent instrument as a CAPI ensures that skips are correctly administered and all questions are answered. In addition, it eliminates the need for editing by the site coordinator and coding and data entry at the home office. The CAPI will be programmed in both English and Spanish.

Using ACASI for the Self-Description Questionnaire and CAPI for the parent interview and the child assessment cognitive subtests will reduce the time the interviewers take to verify that each instrument was administered correctly and thus reduce respondent burden.

A.4 Efforts to Identify Duplication

In the late 1990’s, the US General Accounting Office (GAO) released two reports concluding that (1) “…the Federal government’s significant financial investment in the Head Start program, including plans to increase the number of children served and enhance the quality of the program, warrants definitive research studies, even though they can be costly” (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1998)and (2) this information need could not be met because “…the body of research on current Head Start is insufficient to draw conclusions about the impact of the national program”(U.S. General Accounting Office, 1997).

One purpose of the Head Start Impact Study was to measure the impact of Head Start on children’s early development and school readiness. The Third Grade Follow-Up Study allows us to build upon the existing HSIS design and determine the longer term impact of Head Start on the well-being of children and families. Specifically, the study will examine the degree to which the impacts of Head Start on initial school readiness are maintained or changed by children’s school experiences and the various school quality and family/community factors that come into play up to and during third grade. Other studies have examined third-grade performance and growth but no study has measured the impacts of the Head Start program at the third grade level using a randomized design and a nationally representative sample.

A.5 Minimizing Impact on Small Businesses or Other Small Entities

No small businesses or other small entities will be involved in the data collection for the Third Grade Follow-Up Study.

A.6 Consequences If the Collection Is Not Conducted

As recommended by the Government Accounting Office and mandated by Congress, “definitive research studies” are legislatively required to assess the effectiveness of Head Start nationally on the school readiness of participating children. Despite increasing expenditures, including an appropriation of $6.84 billion in fiscal year 2005, “the body of research on current Head Start is insufficient to draw conclusions about the impact of the national program.” The Head Start Impact Study provided the data to allow such an evaluation through first grade. The Third Grade Follow-Up Study will provide data for determining longer term impacts. If this study is not conducted, there is not a current mechanism determining the long term impact that Head Start has on enhancing a child’s school readiness and performance.

A.7 Special Circumstances

This Third Grade Follow-Up Study will be conducted in a manner entirely consistent with the guidelines in Title 5, Section 1320.6 of the Code of Federal Regulations. There are no special circumstances that might require deviation from these guidelines.

A.8 Consultation with Persons Outside the Agency

The public announcement for the Third Grade Follow-Up to the Head Start Impact Study was published in the Federal Register on Tuesday, August 15, 2006 (Vol. 71, No. 157, pp 46916-46917). The text of the announcement is contained in Appendix B. A single comment was received from the public through this notice. That comment, and our response, is included in Appendix C.

Information concerning the Head Start Impact Study was included in the “Report of the Advisory Committee on Head Start Research and Evaluation” as part of the Head Start Amendments of 1998. The Head Start Act was reauthorized, through fiscal year 2003, by the Coats Human Services Amendments of 1998, PL 105-285 (10/27/98). Consultation meetings were held with Advisory Committee on Head Start Research and Evaluation on January 12, 2001, June 16-17, 2003, and September 28-29, 2005. (Advisory Committee Members are listed in Appendix D.) In addition, a consultation meeting was held with the Advisory Committee on Head Start Accountability and Educational Performance Measures on June 16, 2005. The purpose of these meetings included providing and discussing information about the proposed design and its implementation, instrumentation, and analysis and reporting, as well as general advice from the Advisory Committee Members.

In addition to the Advisory Committees, Westat assembled a consultant cadre to assist the project team in the development of the initial design for the Head Start Impact Study in the areas of assessment of Spanish-speaking children, socio-emotional development, language and literacy, parenting skills and activities, comprehensive services, educational components and observations, and statistics and analysis. Consultants were used to augment the skills and experiences of the project team on particularly difficult technical and substantive issues. Most consultation meetings were conducted as conference calls, however, an analysis consultation meeting was convened on May 7, 2003 to assist the project in designing the complicated analysis plans.

A list of suggested consultants for the Third Grade Follow-Up to the Head Start Impact Study have been submitted to the Program Officer. To date, Westat staff have met with the following consultants to discuss the overall research and design issues for this study:

Mark Greenburg, Pennsylvania State University

Robert Pianta, University of Virginia

Marty Zaslow, Child Trends

A.9 Remuneration to Respondents

In order to minimize the burden placed on families for participating in the study and to maximize response rates, we will provide parents with $50, provided in two installments, for completing both a tracking interview and complete parent interview. A gift card or cash will be provided to the parent upon completion of their interview ($30) and each tracking update ($20). Tracking updates are only conducted during the time periods when full interviews are not administered. A family can receive no more than $50 in two installments over one school year for completing both a tracking interview and complete parent interview. This is an increase in the remuneration for the parent interview but it is important to underscore the fact that this is a new and different study from the original HSIS for families who had begun to experience respondent fatigue. The new incentive should emphasize the importance of the new study and the value of the respondent’s participation in it. We will use the same remuneration plan for the teachers as was implemented in the HSIS (i.e., completed teacher survey and teacher/child rating form(s)). The remuneration was graduated depending on the number of child forms completed: $15 for the teacher survey and 1-3 child forms, $25 for the survey and 4-10 child forms, and $35 for the survey and 11+ child forms. We anticipate that most teachers will receive an incentive of $15. We do not plan to offer remuneration for the principal survey as we do not feel that an incentive is necessary for administrators at this level. Children will receive a non-cash incentive not to exceed $5 to enhance their interest, increase motivation, and ensure high rates of participation. Table 4 provides a summary of the data collection instruments, activities, and incentives.

Table 4. Data Collection Instruments and Activities

|

|

|

Cash/Gift

Card |

|

|

Parent Interview |

Parent/Primary Caregiver |

In-person Interview

Tracking Update Telephone Interview |

$30

$20 |

Interviewer/ |

1 hour

10 minutes |

Child Assessment |

Child |

Individual Assessment |

Non-cash incentive not to exceed $5 |

Interviewer/ Assessor |

1 hour |

Teacher Survey and Teacher Child Rating Reports (TCRs) |

Teacher (Third Grade Reading and Math Teacher) |

Self-administered Survey Individual Child Ratings 1 - 3 children 4 - 10 children 11 + children |

$15 $25 $35 |

Delivered and Collected by Interviewer/ Assessor |

30 minutes for the teacher survey and the teacher/child rating form |

Principal Survey |

School Principal |

Self-administered Survey |

$0 (no remuneration) |

Delivered and Collected by Interviewer/ Assessor |

20 minutes |

A.10 Assurances of Privacy

All Westat staff members sign the Westat pledge of privacy for the study. In addition, all field staff signed a privacy pledge.

For some parent respondents, the issue of privacy of information, particularly relating to address and telephone information collected for later tracing of respondents, is a matter of great concern. Participants will be assured that the information collected will be used for research purposes only by the research team, and that contact name and address information and other survey data will not be given to bill collectors, legal officials, other family members, etc. Also, names will not be linked to the survey in any way. Similarly, program staff will be assured that no information on individual schools or classrooms, including the identity of individual teachers or principals, will be released.

We will implement procedural steps, similar to the steps used in the HSIS, to increase respondent confidence in our privacy procedures. We will generate a set of identification labels with a unique respondent ID number and bar code. These labels will be affixed to each of the data collection instruments for a respondent. The use of bar codes in conjunction with the numbered identification labels enables the receipt control staff to enter cases by reading the bar code with a wand, making receipt of completed interview packages also more efficient.

A.11 Questions of a Sensitive Nature

In order to achieve the goal of enhancing the cognitive and social competencies of children from low-income families, Head Start needs to understand the social context within which Head Start children and their families live as the child progresses through school and the nature of the daily challenges that they face. Thus, several questions of a sensitive nature are included in the parent interview.

Queries of a sensitive nature include questions about feelings of depression, use of services for emotional or mental health problems or use of services for personal problems such as family violence or substance abuse. The questions obtain important information for understanding family needs and for describing Head Start's long term impact in these aspects of individual and family functioning.

Questions about the respondent's neighborhood may also be sensitive but are important to obtain information about the contextual factors in communities that impede or facilitate family well-being.

Another set of questions of a sensitive nature focuses on the families' involvement with the criminal justice system and the child's exposure to neighborhood or domestic violence. Although highly sensitive, this information is crucial to understanding family needs, identifying risk factors for the child's development and fully describing the contextual factors in families that impede or facilitate family well-being. This issue was given a high priority by the National Academy of Sciences (Beyond the Blueprint: Directions for Head Start Research) in formulating recommendations for Head Start research initiatives. A full understanding of these issues is essential both for Head Start program planning and for a realistic assessment of what Head Start can achieve over the long term.

The purpose of the interview and how the data will be used will be explained to all participants. Participants will be reassured in person and in writing that their participation in the study is completely voluntary. A decision not to participate will not affect their standing in any government program, and if they choose to participate, they may refuse to answer any question they find intrusive. All individuals’ interview responses will be private and none of their answers will be reported to any program, agency, or school but will be combined with the responses of others so that individuals cannot be identified. All interviews will take place in a setting where the respondent's privacy can be assured.

The voluntary nature of the questions and the privacy of the respondent's answers will be restated prior to asking sensitive questions. In all cases, questions on these topics are part of a standardized measure or have been carefully pretested or used extensively in prior studies with no evidence of harm.

A.12 Respondent Burden

Tables 5a-c present data on the total burden for respondents to the Head Start Impact Study for each data collection point. For the two years of data collection the average number of responses is 12,850 and the average annual hours requested is 6,873 (as shown in table 5c).

Table 5a. Estimated Response Burden for Respondents in the Third Grade Follow-Up to the Head Start Impact Study-Spring 2007 (Year 1)

INSTRUMENTS |

NUMBER OF RESPONDENTS |

NUMBER OF RESPONSES PER RESPONDENT |

AVERAGE BURDEN HOURS PER RESPONSE |

TOTAL BURDEN HOURS |

Parent Tracking Interview |

4,667 |

1 |

1/6 |

778 |

Parent Interview |

1,720 |

1 |

1 |

1,720 |

Child Assessment |

1,720 |

1 |

1 |

1,720 |

Teacher Survey/TCR |

2,580 |

1 |

1/2 |

1,290 |

Principal Survey

|

1,462 |

1 |

1/3 |

487 |

Totals for Spring 2007 |

12,149 |

|

|

5,995 |

Total Respondents for Year 1: 12,149

Total Responses for Year 1: 12,149

Total Burden Hours for Year 5,995

Table 5b. Estimated Response Burden for Respondents in the Third Grade Follow-Up to the Head Start Impact Study-Fall and Spring 2008 (Year 2)

INSTRUMENTS |

NUMBER OF RESPONDENTS |

NUMBER OF RESPONSES PER RESPONDENT |

AVERAGE BURDEN HOURS PER RESPONSE |

TOTAL BURDEN HOURS |

Parent Tracking Interview |

4,667 |

1 |

1/3 |

1556 |

Parent Interview |

2,042 |

1 |

1 |

2,042 |

Child Assessment |

2,042 |

1 |

1 |

2,042 |

Teacher Survey/TCR |

3,063 |

1 |

1/2 |

1,532 |

Principal Survey |

1,736 |

1 |

1/3 |

579 |

Totals for Spring 2008 |

13,550 |

|

|

7,751 |

Total Respondents for Year 2: 13,550

Total Responses for Year 2: 13,550

Total Burden Hours for Year 2: 7,751

Table 5c. Average Annual Estimated Response Burden for Respondents in the Third Grade Follow-Up to the Head Start Impact Study-Fall and Spring 2008 (average across both years of the study)

Total Average Respondents across Both Years: 12,850 Total Average Responses across Both Years: 12,850 Total Average Burden Hours across Both Years: 6,873

|

Respondents |

Burden Hours |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Annual Avg |

Annual Avg |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Child Assessment |

1881 |

|

1881 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Principal Survey |

1599 |

|

533 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Parent Assessment |

1881 |

|

1881 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Parent Tracking |

4667 |

|

1167 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Teacher Survey |

2822 |

|

1411 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

12850 |

|

6873 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SUPPORTING STATEMENT |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Year 1 |

12,149 |

|

5,995 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Year 2 |

13,550 |

|

7,751 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Average |

12849.5 |

|

6873 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A.13 Total Annual Cost Burden

There are no direct monetary costs to participants other than their time to participate in the study.

A.14 Annualized Cost to the Government

The total cost to the Federal Government for the Third Grade Follow-Up to the Head Start Impact Study, under the terms of the contract to Westat is $9,594,875. These costs include development of the project materials, the use of consultants, data collection, data coding and analysis and preparation of the necessary reports and presentations. Respondent expenses and incentives are included in these costs. The budget breakdown by year follows: Year 1 - $3,663,719; Year 2 - $4,374,500; and Year 3 - $1,556,656.

A.15 Reasons for Any Program Changes

There are no planned program changes. OMB will be promptly notified if any changes are recommended by outside consultants or identified by project staff.

A.16 Plans for Tabulation and Statistical Analysis and Time Schedule

Analysis Plan

The analysis of the Third Grade Follow-Up Study data will begin with an analysis of children’s educational experiences from the third grade through the initial random assignment at the time of application to Head Start. This will consist of both descriptive analyses and experimental estimates of the impact of access to Head Start on the nature and quality of children’s early school experiences, should Head Start influence which schools and classrooms children attend during their early elementary school years. The descriptive piece will be enriched, to capitalize on the opportunity that will now emerge, and that in general is quite rare, to track a large sample of disadvantaged children through several years of early elementary school experience. These analyses will help the reader understand the context within which the many important influences on child development—including Head Start’s impact—guide students’ social and intellectual development during the critical kindergarten to third grade years.

We could also envision that Head Start would change the school experience of the children given access to the program in their pre-school years. The HSIS consisted of two groups of randomly assigned children—a 3-year and a 4-year old cohort of Head Start eligible children who had no prior Head Start experience at the time of random assignment. The 4-year old cohort had the opportunity for, and was observed, during one year of “preschool experience” followed by kindergarten, first and now third grade in elementary school; on the other hand, the 3-year old cohort had the opportunity for, and was observed, during 2 years of “preschool experience” followed by kindergarten, first and now third grade in elementary school. Random assignment at the time of application to Head Start to either the treatment or control group can have an impact on child and parent outcomes by changing where children go (i.e., what we call their “setting”) as well as what they experience once they are in a particular setting. For example, parents may have made different decisions about their child’s preschool experiences as a consequence of being assigned to the control group. These changes, or other shifts in parental perspectives, could also influence where to send a child for elementary school, meaning that access to Head Start could alter the identity of the schools and classrooms children attend once they enter kindergarten and hence the nature and quality of that school experience. The first focus of our analysis of Head Start’s impact involving the Third Grade Follow-Up Study data will explore whether treatment status influenced how school experiences evolved over time for both age cohorts through the end of third grade.

These analyses will consist of the preparation of tables such as the one illustrated (using hypothetical data) in Table 6. In this example, access to Head Start has an impact on the quality of children’s elementary school teacher, possibly by increasing the salience of education to primary caregivers and thus better preparing parents to advocate for a particular teacher for their child at the school s/he attends, and by possibly inducing some parents to select different schools for their children (e.g., non-sectarian or religiously affiliated private schools, charter schools, or even obtaining school vouchers where available).2 Should such events take place as a consequence of Head Start, their cumulative effect on the quality of the elementary education received by former Head Start students would have obvious policy importance (for both Head Start and the public schools that serve Head Start participants) and could strongly affect the mediational influence of the school experiences on the long-run benefits to children of early participation in Head Start.

As shown in the table, access to Head Start (hypothetically) leads 12 percent more of the children to be in elementary school classrooms with high quality teachers, and 6 percent more to be in classrooms with medium quality teachers. Because all of the children from the program and control groups are included in this comparison, these shifts in exposure represent experimental estimates of the impact of Head Start on subsequent in-school experiences. Such analyses can be conducted on a wide range of school experience measures once all children

Table 6. Hypothetical Example: Impact of Head Start on Access to “Quality” Elementary School Teachers

Teacher Qualifications |

Complete Program and Control Groups |

||

Percent of Control (C) Group |

Percent of Program (P) Group |

Change Due to Access to Head Start (P-C Difference=Impact) |

|

Have teacher with |

54% |

66% |

12% |

Have teacher with |

15% |

21% |

6% |

Have teacher with |

31% |

13% |

-18% |

Total |

100% |

100% |

|

are in school (i.e., have data on each measure) to measure directly ITT (impacts on the treated) impacts of Head Start on such important school and classroom characteristics as the child-teach ratio, quality of the instruction children receive, the availability of extra-curricular activities, etc.

Annual Impacts on Child and Parent Outcomes

After examining the nature of children’s in-school experiences that will condition all other outcomes for the study, we will turn to the analysis of cognitive and behavioral development and health, and Head Start’s impact on those outcomes, through the end of third grade. This will provide a longer-term perspective on how Head Start influences child and parent outcomes, extending the kindergarten and first grade analyses of the original HSIS into the core elementary school years. These analyses will deal with what we have referred to as the “main” intent to treat (ITT) impact estimates3 focusing on topics inspired by the research questions recommended for the original study by the National Advisory Panel: “What difference does Head Start make to key outcomes of development and learning (and in particular, the multiple domains of school readiness) for low-income children? What difference does Head Start make to parental practices that contribute to children’s school readiness?” These overarching questions lead to the following research questions as concerns the third grade experience and outcomes of the original study:

Direct Impact of Head Start on Children

What is the impact of access to Head Start during the pre-school years on the extent of children’s cognitive development at the end of third grade? If an impact is found at the end of third grade, it can be due to the carryover consequences of school readiness gains in place as of the spring prior to kindergarten on third grade. Additionally, the impact may be due to the fact that children are fundamentally changed by the Head Start experience in ways that lead them to react differently to subsequent educational experiences. The ITT analysis will measure the combined effect of these two channels through which impacts may appear. A potential additional analysis, if there is interest, would be to try and disentangle the influences from these two separate sets of situations.

What is the impact of prior access to Head Start during the pre-school years on the extent of children’s social-emotional development at the end of third grade? Similar teasing out of the origins and channels of cognitive impacts could also be considered in the case of social-emotional impacts.

What is the impact of prior access to Head Start during the pre-school years on children’s health status at the end of third grade?

Potential Indirect Impact of Head Start on Children Through Direct Impacts on Parents

What is the impact of prior access to Head Start on parent’s practices and support of their child’s education at the end of third grade?

The Final Report from the HSIS will have addressed similar questions through the end of first grade examining all of the outcomes collected through that point. The extension of the study through the end of third grade will augment these early findings by doing the following:

Allowing the examination of how children’s experiences, and impacts on child and parent outcomes, might change as children continue their education through the end of third grade; such changes could occur for example because higher order skills are measured in third grade.

Expanding the range of possible measures of children’s experiences to encompass third grade school experiences, and new parent and child outcomes.

The types of analyses that will be used to answer these newly framed questions collected are described below.

To ensure consistency with the original study, estimates of the main impact of access to Head Start will be estimated for all outcome measures collected at the end of third grade and will be derived using, the same basic statistical model used by the initial study to estimate impacts through the end of first grade:

(1) Yi = 0 + 1 Zi + 2 Wi + 3 Ai + ei where

Yi = spring outcome measure for individual i

Zi = binary treatment variable with Zi=0 if the student is assigned to the control group and Zi = 1 if the student is assigned to the treatment group,

Wi = background characteristics of individual i used as covariates, from Fall 2002 data collection (e.g., race/ethnicity, gender)

Ai = age of individual i on day of outcome data collection, in days

ei = random error term attributable to sampling variation.

The coefficient on the treatment variable, 1, measures the effect of access to Head Start on the outcome variable Y for the average child in the treatment group—the ITT impact estimate. The background variables in W increase the statistical precision of the model and hence the impact estimate, while the inclusion of Ai “neutralizes” any developmental difference between treatment and control group children at the time Yi was measured. The particular set of background characteristics used as covariates in the model, the Wi, will parallel those used in analyses conducted through the end of first grade but will be refined to any other background variables thought to be important conditioning factors for child and parent outcomes at an older age. All will still need to have been measured at the time of random assignment in 2002, such as child gender, child race/ethnicity, whether mother was a teen when she gave birth to the study child, whether the child lives with both biological parents, mother’s highest level of education, whether mother was a recent immigrant, home language, mother’s marital status, child’s age in months as of September 1 2002, parent/primary caregiver’s age, time of fall 2002 testing, and the baseline measure of the outcome variable.

Where available, the fall 2002 baseline measure of the outcome variable Y will also be entered into the equation, since it too can explain a lot of the child-to-child variability in Y and hence increase the statistical precision of the impact estimate. The residualized version of the “pre-test” value of Y will be used for this purpose, to assure that no early effects of Head Start are removed from the longer-term estimates should late (i.e., post-random assignment) collection of this measure in Fall 2002 lead to small treatment-control differences in the measure due to very early program impacts.4 The residualizing assures that these impacts are not removed in calculating later program effects where the pretest is used as a covariate in the model.